Rabu, 31 Agustus 2011

The Two Most Dangerous Words in Technology Marketing

So powerful. So easy to say. So appealing when your current products are behind the curve, and the press and analysts are beating you up about it. You can shut up the critics instantly if you just drop a few hints about the next generation product that's now in the labs.

So dangerous.

The phrase "just wait" ought to be locked behind glass in the marketing department, like a fire extinguisher, with a sign that says, "Break glass only in emergency." And then you hide the hammer someplace where no one can find it.

Saying "just wait" is dangerous because it invites customers to stop buying your current products. You're basically advertising against yourself. If your company is under financial or competitive stress, the risk is even greater because people are already questioning your viability.

This danger is especially potent in the tech industry (as opposed to carpeting or detergent) because tech customers worship newness, and they use the Internet aggressively to spread information. One vague hint at a conference in Japan can turn into a worldwide product announcement overnight.

This danger has been well understood in the tech industry dating at least back to 1983, when portable computing pioneer Adam Osborne supposedly helped destroy his PC company by pre-announcing a new generation of computers before they were ready to ship (link). Palm reinforced the lesson in 2000 by pre-announcing the m500 handheld line and stalling current sales (link).

But maybe memories have faded, because we've been hearing "just wait" a lot lately:

--Nokia announced that it's switching its software to Windows Phone, and promised new devices based on the OS by this fall. Nokia executives have hammered that message over and over, even making detailed promises about features including ease of use, battery life, imaging, voice commands, cloud services, and price (link). Some execs have even told audiences that they have a prototype in their pockets, but coyly refused to show it (link). What's the thinking here? Does refusing to show the product somehow nullify the fact that you just told everyone not to buy what you sell today?

--In February 2011, HP pre-announced a series of new smartphones that were supposed to come out over the next year. The most attractive-sounding one, the Pre3, was supposed to ship last. Not only did this obsolete HP's current products, but it also overshadowed the other new products HP launched in the interim. HP's interim smartphone sales turned out to be so bad that it killed the business before the Pre3 could even launch in the US.

--Speaking of HP, the company just announced that it will be selling its PC business because it's not doing well. As Jean-Louis Gassee pointed out, that's like inviting customers to switch to another vendor who actually wants to be in the business (link). That forced HP executive Todd Bradley to boost confidence by going on tour pre-announcing himself as future CEO of the theoretical spun-out company, even though HP's Board won't even meet to decide on a spinout until December (link).

--RIM announced that it's moving BlackBerry to a new operating system, which will apparently not run on its existing smartphones. It has spent much of the last year telling people how great all the new features of the OS will be. The company also pre-announced that it will enable Android applications to run on its future phones. Meanwhile, market share of its current products has been dropping steadily. The latest rumors say RIM's new phones will not be out until Q1 of 2012 (link), meaning the company has probably sabotaged its own Christmas sales for 2011.

--Microsoft announced that it's replacing Windows in about a year. That's not necessarily a problem, since it says the new version of Windows will run on existing hardware. But Microsoft also said it's introducing a new development platform based on HTML 5. This set off a huge amount of teeth-gnashing among today's app developers worried that their skills are about to become obsolete (check out the excellent overview by Mary-Jo Foley here).

Why are companies doing this over and over? Sometimes you have no choice. For example, Nokia couldn't lay off the Symbian team without saying something about its OS plans. However, it didn't have to be so noisy about the plans, so I think that wasn't its only motivation.

Sometimes the cause is a mismatch between the needs of a hardware business and the needs of a software business. If you're making a software platform, you pre-announce it as early as possible to build confidence and get developers ready at launch. But if you're selling hardware, you want to keep new stuff a secret until the day you ship. When you mix hardware and software, you are pulled in both directions. I think that disconnect probably affected Nokia, which is now run by a CEO who worked in software for most of his career.

Companies also sometimes pre-announce products because it placates investors. Wall Street analysts always ask what you're developing in the future, and executives sometimes can't resist the urge to tell them and prop up the stock price. Ironically, this may help the stock for a quarter, but often has the long-term effect of hurting a company's value when the pre-announcement slows sales. But each CEO always seems to believe he or she will be the one who gets away with it. I believe investor pressure was one of the drivers when Palm pre-announced the m500, and I believe it also explains some of the pre-announcements by HP and RIM.

Sometimes internal company politics also plays a role. An executive may pre-announce a product in the hope that the announcement will put more pressure on the development team to deliver "on time." Or a business leader will pre-announce something to pre-empt internal competition from another group. I've seen both of those happen at places where I worked. Needless to say, any company that allows internal politics to drive external communication has much bigger problems than its announcements policy.

Pre-announcements also create other problems. They educate the competition about what you're doing, and give them time to prepare a response. This is especially dangerous if you're trying to come from behind, which is usually the situation when a company pre-announces. So a competitor is already out-maneuvering you, and now you're giving them more notice of your plans?

But I think the worst effect of a pre-announcement is that it invalidates any signals you get from the market. You can't actually tell if your underlying business is healthy or not. Did HP's smartphone sales slow down because people hated its products, or because HP had invited customers to wait for the new ones? Have BlackBerry sales been suffering because customers don't want them, or because RIM invited people not to buy? Was the enormous drop in Nokia smartphone sales due to flaws in the products, or due to Nokia's relentless promotion of new phones that aren't yet shipping?

There's no way to tell for sure. And so, if you're running one of those companies, you don't know whether or not you should panic -- or more to the point, what exactly you should panic about. You have now trapped yourself in limbo, and there is no way out until your new products ship.

So, as you can guess, I am generally against pre-announcements. But they can be very powerful, and there are a couple of special cases in which they're appropriate.

When it's safe to pre-announce

If you're entering a new business. If you don't have any current sales to cannibalize, it's relatively safe to pre-announce. You're still alerting the competition, which I dislike, but at least you won't tank your current business. Apple pre-announced the first iPhone and iPad before they shipped, but you'll notice that they've been very secretive about the follow-ons.

A variant on this is when a competitor is ahead of you in a new category and you want to slow down their momentum. You pre-announce your own version of their product, in the hope that customers will wait to get it from you rather than buying from the competition. This can be especially effective in enterprise markets, where IT managers tend to develop long-term buying relationships with a few vendors. IBM used this technique relentlessly during the mainframe era, and Microsoft picked up the habit from them.

Pre-announcements are less effective against competitors in consumer markets, where people are sometimes driven by the urge to buy now. They also don't do much in cases where it's easy to switch vendors. For example, Google pre-announcing a web service isn't likely to stop people from using competitors to it in the interim. A pre-announcement can intimidate venture capitalists, though, and I wonder if Google doesn't sometimes announce a direction in order to hinder a potential competitor's ability to raise money.

If there is a seamless, zero-hassle upgrade path. If customers will be able to move easily to your new products, without obsoleting what they use today, and without big expense, a pre-announcement can be safe. For example Apple generally pre-announces new versions of Mac OS, and it's not a major problem because currently-available Mac hardware can run the new OS. Where RIM went wrong with its OS announcement is that its current hardware apparently can't run the new OS. So RIM has announced the pending obsolescence of everything it sells today.

If you are messing with the mind of a competitor. Theoretically, if you're dealing with a competitor who's very imitative, you can make them waste time and money by leaking news of future products that you don't actually plan to build. The competitor will feel obligated to spin up a business unit to copy your phantom product, leaving less money to respond to what you're actually doing.

When I was at Apple, we used to joke that we could waste $20 million a pop at Microsoft by seeding and then strenuously denying rumors that we were working on weird but plausible products. Handheld game machines, anyone? Television remote controls? Apple today is so influential that it could manipulate entire industries by doing that, not just individual companies.

But when you do this you gradually erode your credibility with your customers. If the rumor is plausible enough to dupe a competitor, it will also dupe some customers, who will then be disappointed when you don't deliver. Eventually you won't be able to get customers excited when you announce real products. Look at the skepticism people often express today when Google announces a new initiative.

The most famous case in which misdirection supposedly worked was not in business but in international politics. Some historians say that the collapse of the Soviet Union was hastened by the huge investments it made trying to keep up with Reagan Administration defense initiatives, some of which had no hope of actually working, but which still seemed plausible enough that the Soviets felt obligated to cover them.

I'm not so sure that really caused the collapse of the Soviet Union; big economic changes are usually driven by big economic forces, not by tactics. But more to the point, you're not Ronald Reagan, this isn't the Cold War, and if you try to pull off a fake this complicated you'll probably just confuse your customers and employees.

So unless you're entering a new market, or have a seamless low-cost upgrade path to the new product, your best bet is to grit your teeth, shut up, and next time plan better so you'll be ahead of the market instead of playing catch-up.

Selasa, 30 Agustus 2011

Allowing underwater borrowers to refinance could help

Senin, 29 Agustus 2011

Top 10 Least-Polluting U.S. Metros

Top 10 Least-Polluting U.S. Metros: As greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction policies

gain momentum at the federal and metropolitan levels, a new study about urban

areas’ GHG emissions levels could have implications for real estate

developers.

It is stirking that LA is among the best 10, and is not materially different from Portland and is even a little better than Boston and Seattle. To be fair, the climate here is mild in both winter and summer (while it can get hot during the day, it almost always cools into the 60s or lower at night), and this allows us to avoid cranking up furnaces and air conditioners. But Portland and Seattle have pretty mild climates, too.

One could argue (and some have), that LA has accomplished this by being anti-business, hence driving polluters--along with their jobs--to other states. This may be correct, but ultimately, everyone is going to have to control carbon emissions. Perhaps this will give LA a first mover advantage.

Kamis, 25 Agustus 2011

What does Warren Buffett know?

I thought perhaps that Buffett had hired an army of analysts to go through the securities and figure out their value. But Nicholas Santiago (h/t Yves Smith) has the more likely explanation:

3. Warren Buffett has made a career of investing in troubled companies for the sake of the economy. The last time he made an investment such as this one was back in 2008 with Goldman Sachs Group Inc.(NYSE:GS). It is important to remember that Goldman Sachs was bailed out by the tax payer in what was called the TARP program. Buffett knows that the U.S. taxpayer will bail him out if he is wrong and Bank of America stock does go belly up.[Disclosure: I own a few shares of Berkshire-Hathaway B-shares].

Robert E. McCormick and Robert D. Tollison on the NCAA's Subversion of the Academy

Two great American institutions are about to crank up. Freshman and their older classmates will soon start returning to campuses for fall classes. Soon thereafter or about the same time, fans will fill stadiums and the 2011 college football season will begin. These two events come together almost naturally and have for over 100 years. The former may be one of the best examples anywhere of competition among universities and colleges, but the latter is surely one of the best examples of a cartel. Recent athletic resignations and firings at Ohio State, Georgia Tech, and now most recently the University of North Carolina demonstrate that the corrupting influences of the NCAA cartel on the academy have reached the highest levels of our public universities. Doubtless there are few people on earth who care less about the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill than us (since it is a prime competitor in intercollegiate sports), but in spite of this, the time has come to stand up and be counted on the athletic scandal that has engulfed UNC-CH and so many other institutions of higher learning in our country (including Georgia Tech and Ohio State). UNC-CH is not just a university, it is regularly rated as one of the top five public universities in the United States.The passage that really hits home to me is: "Students are being taught that ends matter, but means do not. Our educational system is built upon honor, integrity, and the search for truth as bedrocks. Yet these same foundations are washed away on a regular basis by phenomenal dollars made available by the cartel. What is a young person to believe?"

What is the root of the problem here? We assert it is the enormous economic rents, or free money, that have been created by the NCAA cartel. Moreover, no college or university can be expected to withstand the ill-gotten gain that lurks underneath the NCAA banner. The NCAA is a cartel of the major athletic universities in the United States that sets wages, playing conditions, and other aspects of intercollegiate athletics. Most prominently of these is a restriction on payments to football and basketball players. These two sports create billions of dollars in local and national revenues via gate receipts, TV contracts, and ancillary merchandise, not to mention millions of dollars annually at member schools in donations by alumni and other supporters of athletic programs.

Coaches sign multi-year multi-million dollar contracts while players get tuition, room and board, and recently, only because of an important court case (White v. NCAA), some pocket money to cover the cost of living. Big chunks of these revenues also go to support other men and women athletic teams on campuses, swimming, track, golf, soccer, and the like. None of this would be possible but for the overarching cartel agreement between all of the major U.S. colleges and universities operated under the umbrella of the NCAA.

Both of us have long held, along with numerous other economists (such as Gary Becker and Robert Barro), that the NCAA’s cartel harms the market, the world, and the athletes, but now we are prepared to claim more. To wit, this crisis in athletics puts the American system of higher education at risk.

Despite our earlier disclaimer, UNC-CH is an incredible academic institution, a virtual colossus of graduate education, research, and professional education. Yet with all its storied history and social importance, the school has put its institutional credibility and brand name at risk by succumbing to the perverse incentives created by the cartel, a cartel whose primary function is to maintain a façade of amateurism on the one hand while aggressively pursuing commercial profits on the other. Never mind the morality of the arrangement. Focus instead on what this temptation has done to the University, and remember that this has been happening at lesser schools for a long time. Now that it has reached the ranks of most elite universities, it is hard to argue that any school is immune from becoming ensnared in the inevitable trap that lies in the huge gulf between amateur inputs (the lowly paid players) and professional outputs (massive TV contracts, alumni donations, and ticket prices).

Hear us clearly, we are NOT arguing to pay players. We are lamenting the diminution of the reputation of a top ranked public university and the warning signal that it sends about the dangers of the incentives created in this case. We believe in amateurism, deeply. But we believe that it should apply broadly to the coaches, the fans, and all the rest of the participants in intercollegiate sports. If amateurism is a shrine, then let us all worship it. The fans should get to see the games for nothing or nearly so (the costs of facilities and game day services). The coaches should be faculty or volunteers as they are in Little League and in local neighborhoods. It is not amateurism, but the business of intercollegiate athletics is a growing cancer bound to infect other storied American institutions of higher education.

Where does the fault lie? It lies plainly on the shoulders of the NCAA cartel. We propose that our school, Clemson, and the rest of the schools in the ACC leave the organization, sit down, take stock and decide whether the Ivy League approach is better for the ACC (no athletic scholarships) or whether the players should receive reasonable compensation. We do not take a position on the issue. Each league within the NCAA should do the same, and we doubt that they will all choose the same course. Some will go the Ivy route, others the payment route. And that is as it should be. There should NOT be one authority in control of almost all collegiate athletics in the United States. Competition is salutary, and it should prevail both on and off the field.

Cartels are a bad bargain. They raise price to consumers, reduce output and social welfare, and enrich one class of participants at the expense of another, creating envy and strife. The NCAA cartel is especially perverse because it disadvantages young people (often from challenging backgrounds) to the advantage of adults. And worse, it is morally corrupting to these same young people, compounded by the fact that it derives from the same university institutions society has charged to nurture them to adulthood.

At present, coaches, even those trying to live by the rules, daily confront moral dilemmas and choices. But the nature of the restrictions creates two sets of rules (written and unwritten), and our young college students, both the athletes and their classmates, are not being taught to play by the rules. They are being taught, “everyone cheats, we got caught, it is no big deal.” Paying under the table is okay. Having tutors write term papers is okay for athletes who are working their rear ends off to practice especially if they are good and the team is winning.

Students are being taught that ends matter, but means do not. Our educational system is built upon honor, integrity, and the search for truth as bedrocks. Yet these same foundations are washed away on a regular basis by phenomenal dollars made available by the cartel. What is a young person to believe? That it is wrong to crib on a test or plagiarize a term paper, but okay to lie to the NCAA investigator? That it is right and proper to offer a helping hand to those less fortunate or in need, but wrong to do so if they have signed an athletic scholarship? Our universities need to stand for our culture, and our culture should not be about lying, half-lying, deviousness, and cheating. There is only one way to end cheating- resolve the conflict between amateurism and professionalism, either by making both sides professional or both sides amateur. But the current situation is unsustainable and puts institutions of higher education at risk.

We contend that the moral fiber of the university is one of its most powerful social virtues. It helps bring young people to adulthood with a care and concern that things are done correctly and on the up and up ethically.

There is a clear positive implication of our argument. Cheating teaches cheating, and it is a mistake to think that our kids will not watch what we do instead of what we say. The scandals that now infect the best universities in the land will almost surely lead to more and more academic dishonesty and disregard for the basic traditions of the academy if something does not happen to reverse course. Cheating in the athletic department begets cheating in the classroom and perhaps generally in life. This is a prediction of our argument albeit a depressing one.

It is critical to note that we are big fans of the coexistence of athletics and academics. Our research speaks loudly and clearly on this. We support athletics as part of university education and think the two together make for the best organizational arrangement. Our cry is NOT about athletics, but about the NCAA cartel that creates the rents and free money that shred the moral underpinnings of our home, the academy.

A la Ronald Reagan, we say tear down the wall around truth and dignity. Clemson, UNC, Georgia Tech, and all the rest should refuse the financial inducements offered by the NCAA. Return to amateur intercollegiate sports, or pay the players. Nothing less than the integrity and quality of our universities is at stake.

Rabu, 24 Agustus 2011

Thanks, Steve

It was the Macintosh computer you championed that first drew me into developing software. That business didn't make me rich, but it eventually got me hired by Apple. Unfortunately, you left a year before I got to Apple, but the company's goals were still the things you preached -- do something insanely great, change the world.

I spent ten years at the company you co-founded, and it was both a great education and a fun ride. Unfortunately, in a case of spectacularly poor judgment, I quit in early 1997, after the NeXT acquisition but before you took back control of the company. I didn't believe you'd take over, and I lost faith in the previous management. My only contact with you was a single meeting that you and I both attended. I was there as an observer, so I sat in the back and said nothing. My only impression of you was, "wow, he really doesn't wear socks."

Perhaps it's just as well that I quit.

Although I was no longer with Apple, you still played a huge role in my career. For a time in the late 1990s, it looked like Silicon Valley was becoming a backwater in technology. Software was dominated by Microsoft after its demolition of Netscape, AOL on the east coast was the online leader, and Dell in Texas plus the Asian companies were the leaders in PC hardware. The Valley's leadership role was saved, I believe, by Yahoo and Google in the web world, and by Apple's resurrection in computer systems.

Other people are doing a great job of recapping all of Apple's product successes since your return, so I won't bother repeating them here. But I want to talk about two other accomplishments that stand out to me. The first is how you've reset the way the tech industry looks at consumer products. Even a few years ago, most people still said that Microsoft's business model -- in which the hardware was designed separately from the software -- was the only viable way to make computing devices. Today, everyone talks about codeveloping hardware and software, and it's because of you.

The other accomplishment that stands out to me is your creation of an organization at Apple that could turn out hit after hit, reliably and with great quality. Most people don't appreciate how hard that is, mostly because Apple makes it look so easy.

It's because of the organization you built that I'm confident Apple will continue to do well, even as you reduce your role. I hope your health will improve, and it would be great to see you back as CEO some day. But that's speculation for another time.

Right now, I just wanted to say thanks, Steve. It was insanely great, and you did indeed change the world.

Selasa, 23 Agustus 2011

Two cents (or maybe a nickel) on Texas.

In an ideal world, we would run some regressions explaining Texas' growth, but we haven't sufficiently up-to-date data to do that. We do know that some things matter in general for growth: climate (which I don't think even Rick Perry is claiming credit for); fraction of the population with a BA, and, if I may refer to work I did five years ago, availability of air transportation.

Texas does well in two out of three indicators: since World War II, people and jobs have moved to warmer places such as Texas, and Dallas is a hub for two airlines and Houston is a hub for one. Texas is below average, however, in the share of adults with BAs and graduate degrees.

So why is Texas doing well? First, it has managed to maintain its state and local government spending far better than most other states, and has not had the negative stimulus arising from massive layoffs. Over the past decade, government job growth in Texas has outpaced private sector job growth by about 2 to 1.

Second, Texas has among the most stringent consumer protection laws in finance in the country--likely arising from a long-standing Western mistrust of bankers. As a consequents, consumers were essentially forbidden from using their homes as piggy banks. As Mike Konczal shows, this means Texans have far less debt to pay off (it also shows how we in California are still in the soup). So "heavy-handed" regulation helped keep Texas out of trouble.

Finally, it is simply easier to develop everything in Texas--housing, businesses, etc. This is the one part of the conservative view of Texas that I buy--as one Los Angeles planner said to me, it takes 18 months in LA to do what it takes six weeks to do in Dallas. LA doesn't even have by-right zoning. It is here where I think Texas has an enormous advantage for business development over California.

That said, California has a greater share of people with BA's than Texas. Part of the reason why may be that well-educated people, who can afford to live in a place that takes environmental protection seriously, do so. There is actually some good reason for California's stringent environmental rules--the air quality here, while much better than it used to be, is still not good enough. Of the ten cities with the worst air quality in the country, six are in California. But the cities with the worst air quality outside of California are Houston and Dallas; someday voters in those cities are going to demand better. I do think California can do a better job of protecting its environment while making business development easier, but that is the subject of another post.

Minggu, 21 Agustus 2011

I'm Speaking at Mobile 2.0

The Mobile 2.0 folks have offered a discount to Mobile Opportunity readers. If you register using the code "TwentyFive" you'll get a 25% discount.

Cost and benefit

Triumph of the Rentier City?

Early on in the book, Ed celebrates the resiliency of Manhattan, noting that "[b]etween 2009 and 2010, as the American economy largely stagnated, wages in Manhattan increased by 11.9 percent, more than any large county."

This passage brought to mind Vernon Henderson's pioneering work on large cities and favoritism. He writes:

This enhanced role of government in the urbanization process over the years has resulted in a corresponding bias, where certain regions and cities are heavily favored in terms of capital and fiscal allocations, giving favored regions a cost advantage.New York is wonderful, but it has been given an enormous cost advantage in the aftermath of the financial crisis. It's institutions received cheap capital in the form of TARP; a near zero Federal Funds Rate also amounts to a large subsidy for financial institutions. Banks can currently make profits just by playing the yield curve. These profits have helped restore Wall Street bonuses (and hence incomes of everyone else in Manhattan), but that doesn't mean they reflect productive activity.

I don't want to make too much of this: TARP was necessary, and the low Federal Funds rate is necessary too. New York is a great and resilient city. But it is also home to many too big to fail institutions, and thus has political and financial advantages that, say, Chicago and San Francisco lack.

Jumat, 19 Agustus 2011

The Part of Palm that Smartphone Companies Should be Bidding For

You can make an argument that HP should have given the business more time, and it's a shame that we'll never get to see the Pre 3. But Palm's sales have been troubled for years, and I think its fundamental mistake was that it tried to be too much like Apple. From the start, Pre was aimed at the same users and the same usages as the iPhone (even down to a failed effort to tie the phone directly to iTunes). HP proved that most people don't want to buy an incremental improvement to the iPhone that can't run iOS apps.

Then just for kicks, HP went and proved the same point again with the TouchPad.

The lesson to other mobile companies, I think, is that unless you're a low-cost Asian vendor, you need to differentiate from Apple, not draft behind it.

I'd love to see Web OS live on, but the hardware debacle makes that less likely. As I mentioned the other day, licensees choose an OS because they think it'll generate a lot of unit sales for them. Since Web OS couldn't do that for HP, who else would want to license it?

If you believe that every smartphone company needs to own its own OS, we ought to see a mad bidding war between LG, HTC, Sony Ericsson, Dell, and maybe Samsung to buy Web OS. (The loser could get RIM as a consolation prize.) Maybe a buyout will still happen, but I think HP has probably been quietly shopping Web OS for a while, and if there were interest it would have tried to close a deal before today's announcement.

(By the way, HTC, if you do buy Web OS, you should insist that HP give you the Palm brand name as well. It's still far better known than the HTC brand in the US. The same logic applies for LG.)

But I'm not persuaded that buying an OS is the right way to go for any smartphone company. Turning yourself into a second-class imitation of Apple isn't a winning strategy, especially if your company doesn't know how to manage an operating system. (Case in point, look what it did to HP.) You can create great mobile systems without controlling the OS; all you need is a great system development team and the freedom to put a software layer on top of whatever OS you use.

That means the real crown jewel in the Web OS business unit is the system development people -- the product managers and engineers -- that HP just threw in the garbage. In my opinion, that's the part of Palm that smartphone companies should be fighting for.

Rabu, 17 Agustus 2011

Even in principle, figuring out a fair tax system is hard

U(X(L)-L-t)/U(X(L)-L) = K

The idea is that the fraction of utility one keeps after taxes is the same for everyone. X is consumption; the amount one gets to consume is a function of effort, L. To make things easy, we will assume people consumer their incomes, so that income and consumption are the same. Assume that utility function has the shape U' > 0 and U" < 0. K is dependent on how much society wishes to spend on public goods.

Just this simple formulation presents three problems. First, the fair rate of progressivity will be a function of the magnitude of U". For instance, if we assume log utility, U' = 1/(X-L) = U" = -1/(X-L)^2. This means U" gets very small very rapidly, which also means that the need to increase marginal tax rates in income to maintain the above definition of fairness gets quite small. We do know that taking money away from people at or below subsistence levels of income will lead to substantial diminution of utility, but beyond that point it is hard to say how sharply progressive taxes need to be in order to be fair.

Second, the correspondence between consumption and effort is not one-to-one. If the correlation between consumption and effort is less than one--and I will go out on a limb and say that it certainly is--taxing income actually only approximates taxing utility. The lower the correlation, the worse the approximation.

Finally, defining effort is a problem. As Matthew Yglesias notes, NYU professors make a lot less money than Wall Street bankers, but their life might well be better. Perhaps I am wrong, but it seems to me that the -L in a steel worker, coal miner, or line worker is a lot bigger than mine, and so looking at income alone is adequate for approximating utility.

So what to do? Here is why, despite my liberal leanings, I find a flat tax with a large exemption and a large earned income tax credit appealing. The rate would have to be sufficient to raise revenue, and would apply equally to all type of income. Deductions would be limited. Such a set up would assure that Warren Buffett would pay no less a share of his income than anyone else. Bob Hall proposed a similar plan 15 years ago. I would dress it up with the earned income tax credit.

Selasa, 16 Agustus 2011

Google and Motorola: What the #@!*%?

Usually when a big tech merger happens you can see the logic behind it. Even if you don't agree with the logic, you understand why they made the deal. But in this case the more I think about it the more confused I get.

Did Google buy Motorola for the patents? If so, why isn't it spinning out the hardware business? Or did Google buy Motorola because it wants to be in the hardware business? If so, does it understand what a world of other problems that will create for Android and the rest of Google? Seriously, if Google tries to integrate Motorola into its business we could end up citing this as the deal that permanently broke Google.

Why roll the dice like that? Maybe I'm missing something, maybe Google has a screw loose, maybe both of the above. Or maybe I'm wrong to look for airtight logic. Companies sometimes make decisions on impulse, especially when they are under stress, and it's a sure thing that Google is under stress these days on IP issues.

So I have a lot more questions than answers. My questions are about Google's intent, its next steps, and how other companies will react...

Why did Google do it, really? The conventional answer is that Google wanted Motorola Mobility for its patents. That's what Google itself implied, and Marguerite Reardon over at CNET agreed (link). That might well be the explanation. Om Malik had a really intriguing take: Google bought Motorola as a defensive move to prevent Microsoft from getting the Motorola patents (link). And Richard Windsor of Nomura, who I respect deeply, said in an e-mail that this is all about the patents. He predicts that Google's new patent portfolio will create a balance of power enabling Google to quickly force a settlement to the patent lawsuits against its licensees.

But if you wanted only the patents, I think you'd buy Motorola, keep the patents and then spin out the hardware company to avoid antagonizing your licensees. Google says it intends to keep Motorola and run it.

Besides, as Andrew Sorkin pointed out in the New York Times, Google could have bought a different but also important mobile patent portfolio from InterDigital for about $10 billion less than Motorola (link). Maybe there's some magic patent at Motorola that Google feels is worth $10 billion more, or maybe there are some terms in Motorola's patent cross-license agreements that Google desperately needs. But again, if that's the case, why not keep the patents and resell the hardware business?

Unless Google is lying about keeping Motorola intact, I think Google intends to be in the mobile hardware business. Which raises the next question...

Does Google know how to run a hardware business? No, of course not. The processes, disciplines, and skills are utterly different. The same business practices that made Google good in software will be a liability in hardware. Google's engineers-first, research driven product management philosophy is effective in the development of web software, because you can run experiments and revise your web app every day in response to user feedback. But in hardware, you have to make feature decisions 18 months before you ship, and you have to live with those decisions for another 18 months while your product sells through. You can't afford to wait for science. Instead, you need dictatorial product managers who operate on artistry and intuition. All of those concepts (dictatorship, artistry, intuition) are anathema to Google's culture. Either Google's worldview will dominate and ruin Motorola, or worse yet the Motorola worldview will infect Google. Google with Motorola inside it is like a python that swallowed a minivan.

To put it another way, I think Google has about as much chance of successfully managing a device business as Nokia had of running an OS business.

But the real question is, does Google realize that it doesn't know how to make hardware? I doubt it. Speaking as someone who worked at PalmSource for its whole independent history, an OS company always believes that it could do a better job of making hardware than its licensees. It's incredibly frustrating to have a vision for what people should do with your software, and then see them screw it up over and over. The temptation is to build some hardware yourself, just to show those idiots how to do it right.

I think maybe Google just gave in to that temptation.

But if Google really wants to sell hardware, that raises questions for the other Android licensees...

How will Google really manage Motorola? Google says it's going to treat Motorola as an independent company without any special access to the Android team. But what's the point in that? Motorola hasn't exactly been dominating the mobile device world lately, so I find it very, very hard to believe that Google would buy it and leave it intact. Wouldn't you want to have Motorola create special products that take advantage of the latest Android features? Kind of like a flagship operation? Then when you announce a new initiative at Google IO, you can have some nice new Motorola hardware ready to ship with it on day one. Of course, the other Android licensees will be allowed to participate too. They're welcome to run flat out to keep up with every Google software initiative, disregarding expense and business risk, just like Google's Motorola subsidiary will.

Which makes you wonder...

How will the Android licensees react? I think we can safely disregard the positive quotes from the other Android licensees. What would you do if your company depended utterly on Android, and Google called you up twelve hours before the announcement and asked for a quote? Would you risk Google's anger by refusing to give a nice quote? Of course not.

But would you honestly be happy? Of course not. In the last year, you gained share at the expense of Motorola. Now instead of being a weak and failing vendor you can snack on, Motorola has infinite financial resources and cannot physically go broke. Sure, I am happy to compete with that.

The other issue is the one everyone else has already pointed out -- even though Google says there will be a firewall between Motorola and Android, you suspect it'll be semi-permeable, meaning you'll always be at a bit of a disadvantage.

So what do you do? A lot of people are predicting that Android could be in danger of losing licensees. For example, Horace Dediu at Asymco drew a parallel to the Symbian consortium, whose members were uncomfortable because Nokia held the largest share of the ownership (link). But when Symbian was launched, those companies were happy to sign up, despite the asymmetric ownership, because they thought Symbian was going to dominate the mobile OS market, and they were scared of Microsoft. They dropped out only after it was proven conclusively that only Nokia was capable of making a Symbian phone that sold well in Europe.

I can tell you from personal experience at Palm that licensees don't care about governance issues when they think your OS will help them sell a lot of units. It's only after growth slows down that they get twitchy. As long as Android continues to grow explosively, the licensees will be right there with it because they're terrified not to be.

Google probably knows the licensees can't go anywhere. In fact, it has a history of treating them very roughly in private (check out the nasty tone in the private memos between Google and Samsung exposed by the Skyhook lawsuit here). So in some ways the Motorola deal is just more of the same.

But there is still a risk to Google. Android licensees will probably be more willing to talk to Microsoft now, and they might do a few more Windows Phone products, if only to get leverage against Google. So Google has just thrown a lifeline to Windows Phone, which otherwise might have been headed for extinction if the first round of Nokia products failed.

This might also be an opportunity for other mobile platforms. If there were any...

Is there a third path? The Android licensees are probably pretty wary of both Google and Microsoft at this point, and may be wishing forlornly that there was a third alternative for mobile operating systems.

Unfortunately, I don't think there is. The handset vendors' embrace of "royalty-free" Android strangled the other Linux mobile platforms. TrollTech was bought by Nokia and then killed, while Access's evolution of Palm OS died for lack of customers.

There's speculation that HP might broadly license Web OS (link). But HP has its own hardware conflict of interest (a much stronger one than either Google or Microsoft). Far more importantly, keep in mind that mobile phone companies license an OS because they believe it's going to sell millions of units for them. If HP, with all of its resources and channel presence and strong brand, can't sell significant numbers of Web OS phones, why would HTC or Samsung believe they could do it?

[Edit: In the original version of this post, I failed to mention MeeGo. A couple of people have told me that was unfair, and I think they are right. Based on past experience, I have a lot of skepticism about OS consortia, especially ones involving Intel. But if MeeGo's ever going to get serious consideration from hardware companies, now is the time, and I should have acknowledged that.]

Hint to Android licensees: If you build up HTML 5 as a platform, you won't have to depend on anyone else's platform. But in the meantime, your realistic choices are Android and Microsoft.

Speaking of Microsoft...

What will Microsoft do now? Steve Ballmer faces a very interesting decision. Windows Phone just got a boost because it's now seen as a more vendor-neutral platform than Android. The door is probably open for Microsoft to build deeper relationships with Android licensees. If Microsoft sill believes in its licensing model, it will focus on walking through that door.

But as others have pointed out, Microsoft's position is now a bit lonely in some ways. The other major smartphone platforms (iOS and Android) now have captive hardware arms. Even RIM has both hardware and OS, although it's been a while since RIM was held up as a model for others to emulate. Will Microsoft feel exposed without its own hardware business? And if it does feel exposed, will it buy Nokia?

I'd be very surprised if it did. Buying Nokia would decisively end the Windows Mobile licensing business. You'd be betting Microsoft's mobile future even more completely on the ability of Nokia to execute in hardware. Besides, why buy the cow when you're already milking it?

I'd also like to think that Microsoft learned from the Zune debacle that it's not great at creating mobile hardware.

And then there's the fruit company...

What will Apple do? Apple's history since Steve returned is that it doesn't react to competitors; it forces competitors to react to it. Apple is brilliant at setting the terms of the competition so other companies are forced to compete on Apple's turf. Everyone else is focused on building licensed commodity hardware, so Apple creates integrated systems. Everyone else has optimized their supply chains to sell through third party retailers, so Apple creates its own stores. Everyone else stopped making touchscreen smartphones, so what does Apple make?

You get the picture. So I don't expect Apple to make any changes in response to the Motorola deal, but I would be shocked if Apple didn't have plans for changing the terms of the competition again now that Google is trying to build more integrated hardware and software. There are all sorts of game-changing moves Apple could make -- do a much larger push in web services, create an iPhone Nano (fewer features and lower price), even create its own search engine or social network (potentially valuable just to make Google crazy).

What's next?

To sum it all up, it's impossible to predict what will happen. Hopefully the new balance of power in patents will make the big lawsuits go away, although I doubt we'd see a resolution before the deal closes, and that could take many months. If Google bought Motorola for the patents, it'll either sell the company or let it gracefully rot, and we'll go back to business as usual.

On the other hand, if Google tries to integrate Motorola into its business, that's a noble mission, and I hope they'll succeed because the mobile industry needs more competition to Apple in systems design. I dearly hope Google will take the challenge seriously and recognize that it'll need to make fundamental changes to its culture. But those changes would be daunting even for a company experienced in mergers, and Google's never done a deal this big before. I think the most likely outcome of the Google-Motorola merger is some flavor of train wreck.

I hope I'm wrong.

Senin, 15 Agustus 2011

Two GOP Governors stuck in a 1950s Economy

Now Rick Perry says in his campaign announcment:

The change we seek will never emanate out of Washington, D.C. It will come from the windswept prairies of Middle America, the farms and factories across this great land, from the hearts and minds of the goodhearted Americans who will accept not a future that is less than our past…patriots who will not be consigned to a fate of less freedom in exchange for more government. We do not have to accept our current circumstances. We will change them. We are Americans.Farms now produce a little more than one percent of GDP. And while the US is still the world's leading manufacturer by output, automation has continued to reduce jobs in manufactuning--a reduction that will continue in the years to come, regardless of the health of the economy.

Where does change come from? From Silicon Valley. From Route 128. From the Research Triangle. From labs at Cal Tech and MIT and, yes, the University of Wisconsin and the University of Texas. Also from Hollywood, from fashion designers in New York, from sneaker designers in Oregon, and, like-it-ot not, from Pharmaceutical Companies in New Jersey, New York and Indianapolis. These are things we do that the rest of the world envies. These are things that happen in cities. And yet not a word about any of it.

PPD 498 Fall Syllabus

University of Southern California

Professor Richard K. Green

richarkg@usc.edu

Keynesian.richard@gmail.com

213-740-4093

This is a senior honors course on topics in Urban Development. This emphasis of the course is on reading, presenting and critically reviewing some classics, old and new, on issues important to those who wish to do research on cities and their regions.

The requirements of the course are three:

(1) Doing the reading before class and participating in class. Your performance in participating will determine 1/3 of your grade.

(2) Leading a ½ hour class discussion on a reading of your choice. You will need to get clearance from me on the reading, and you must let me know your proposed reading by October 1, 2010. This will determine another 1/3 of your grade.

(3) A critical literature review of a topic of interest to you involving an urban topic. The lit review must discuss a minimum of five papers (more would be better) and should be 15-20 double spaced, 12-font, pages long. This will determine the final 1/3 of your grade.

All of USC’s academic conduct rules apply to this course; because you are choosing to be in it, I am assuming this will not be an issue with any of you.

Topics and Readings

August 25 Lenses of Social Science

George Orwell, Why I write.

September 1 New York

Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities I

September 8 Growth in Cities

Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities II

John Quigley (1998) Urban Diversity and Economic Growth, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 12(2):127-38.

September 15 Urbanization and Development

J. Vernon Henderson (2004), Urbanization and Growth, Brown University Working Paper

Marianne Fay and Charlotte Opal (1999), Urbanization without Growth, World Bank Research Working Paper.

September 22 Sprawl

Reid Ewing (1997), Is Los Angeles-Style Sprawl Desirable? Journal of the American Planning Association, 63:1, 107-126.

Peter Gordon and Harry Richardson (1997) Are Compact Cities a Desirable Planning Goal? Journal of the American Planning Association, 63:1, 95-106.

George Galster, Royce Hansen, Michael Ratcliffe, Harold Wolman, Stephen Coleman and Jason Freihage (2001), Wrestling Sprawl to the Ground, Housing Policy Debate, 12(4), 681-717.

September 29 Anti-Sprawl

Ed Glaeser, The Triumph of the City I

October 6 Agglomeration

Ed Glaeser, The Triumph of the City II

Paul Krugman, Development, Geography and Economic Theory

October 13 Guest

October 20 Housing

Stephen Malpezzi (1996) , Housing Prices, Externalities and Regulation in US Metropolitan Areas, Journal of Housing Research, 7(2) 209-242.

Richard K. Green (1996), Should the Stagnant Homeownership Rate be a Source of Concern, Regional Science and Urban Economics.

October 27 Cities and Health

Charles Rosenberg, The Cholera Years.

November 3

William Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis I

November 10

William Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis II

November 17

Student Led Discussions I

December 1

Student Led Discussions II

Minggu, 14 Agustus 2011

Current Construction of the New World Trade Center Site

Is this too much building? Perhaps not. The other contextual number is the amount of current space in Manhattan; the total is about 350 million square feet. So by building a downtown St. Louis, Manhattan is expanding its office market by only two to three percent.

Jeremy Stein for Fed Governor

Personally, I am a big fan of Stein's work. The shortest way to explain why is to list the titles of his five most cited papers:

- Herd Behavior and Investment

- A Unified Theory of Underreaction, Momentum Trading and Overreaction in Asset Markets

- Rick Management: Coordinating Investment and Financing Policies

- Bad News Travels Slowly: Size, Analyst Coverage and the Profitability of Momentum Strategies

- Internal Capital Markets and the Competition for Corporate Resources.

Stein has spent his career trying to figure out how capital markets really work instead of pledging fealty to models that don't work very well. I can't think of a better intellectual qualification for a Federal Reserve Board member.

Jumat, 12 Agustus 2011

William Malkasian

When I think of the people in the world who have taught me a lot, only members of my family supersede Bill. He helped me learn, in the phrase of Paul Krugman, how to "listen to the gentiles." He also helped make me a more sympathetic person, and allowed me to appreciate skills in others that I would otherwise have not appreciated.

Bill is leaving his position as president of the Wisconsin Realtors Association after more than 30 years in order to provide strategic planning consulting to real estate groups around the country (Bill also taught me the value of strategic planning). WRA will miss him a lot, but the rest of the country will be better off.

Kamis, 11 Agustus 2011

DOES HAVING TWO CO-CEOS WORK FOR A COMPANY?

In the weeks that followed the first signs of infertility in the US home mortgage market in the new century, panic gripped boardrooms in America Inc. According to the US Government’s Department of Commerce, these dates correspond to the Aug-Sept months of Q3, 2008. Then, the shock was expected, accepted and came with reasons. [Till Q3, 2009, the US economy continued going downhill with GDP growth recorded in the four quarters leading to Q3, 2009: -2.7%, -5.4%, -6.4% and -0.7%]. Corporations which till then had been a symbol of America shining, had fear in their minds – they wanted to avoid losing the pounds gained since 2001. And those who had been doing quite the opposite, sensed a threat to their very existence. One of them was Motorola.

|

(L-R, starting opposite page): Sanjay Jha (CEO, Motorola Mobility Solutions) & David Brown (CEO, Motorola Solutions) – co-CEOs whose roles and divisions were split after an initial failed start; Anshu Jain & Jurgen Fitschen (Co-CEOs of Deutsche Bank) – an unwelcoming reaction from the stock market on their appointments; and Mike Lazaridis & Jim Balsillie (co-CEOs of the troubled Research-In-Motion) – who will go first? |

Since Motorola became a victim to the co-CEO leadership practice, its decline accelerated. Until Q4, 2010, the company’s share in the worldwide mobile market – despite an 888.8% rise in sales of Android handsets (which was Motorola’s bet) – had fallen to 2.1%. And how did the co-CEOs do worse for the company than the much criticised authoritarian-andbureaucracy- promoting CEO Zander? While under Zander (between Jan 2004 and Jan 2008), the company had gained 1.2% in market share (to touch 17.5% for Q4, 2007), with its m-cap too appreciating by 24.0% to touch $39.01 billion (as on Dec 31, 2007), under the two co- CEOs, within just a year-and-a-half (between Q3, 2008 and Q4, 2010), the company besides losing 7.4% of the global market share, eroded more than half (55.56%) of their shareholders’ wealth – to touch a lowly $9.26 billion as on December 31, 2010. While everyone – from a near-dead HTC to the ever declining Nokia – moved ever so swiftly to capture opportunities in the 4G market, Motorola, under the duo remained every so dedicated to its engineering and careful to market culture [rather, slow – proof is the delayed launches of its Droid Bionic and Xoom 4G update]. This co-CEO arrangement suffered from delays in decision- making. In an interview with BusinessWeek, Jha had confessed that he takes about “90 days to assess a situation before taking any final decision.” Naturally, much time is spent in convincing the other co-CEO – Brown. 90 days to take any call in the world of mobility beats any logic. The Economist, in a Mar 2010 piece titled, ‘The Trouble with Tandems’, puts the problem with co-CEOs theory rightly: “Joint stewardships are all too often a recipe for chaos. Rather than allowing companies to get the best from both bosses, they trigger damaging internal power struggles as each jockeys for the upper hand. Having two people in charge can also make it tougher for boards to hold either to account. At the very least, firms end up footing the bill for two CEO-sized pay packets.”

The shareholders at Motorola (led by Carl Icahn), having finally realised that this joint-leadership is doing no good to them, split Motorola into two separate companies in Jan 4, 2011 – Motorola Solutions (headed by CEO Brown) and Motorola Mobility Holdings (headed by CEO Jha). Going by the financials during the two bygone quarters, it appears that both the companies are en route to safety. After losing $4.29 billion in FY2008 & FY2009, within seven months of the split in roles, it is quite visible that the move is working – the combined net m-cap of the two firms have reached $19.92 billion (a rise of 115.12%), and the two companies have also become more profitable (with a 206.93% y-o-y increase in PAT for H1, FY2011 to touch $709 million). Motorola invented the 6-sigma more than two decades back. It can’t have two CEOs in the name of ensuring quality, and missing out on timely meeting consumer demands. One CEO on top will do.

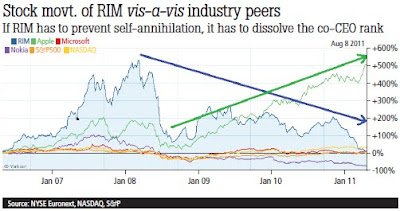

Trouble in cases where joint bosses are calling the shots, is not rare. The most recent instance being that of RIM which is led by co-Chairmen and co-CEOs Mike Lazaridis and Jim Balsillie. While Balsillie is the techie, Lazaridis is the salesguy. This combination was supposed to bring out the best in RIM. It has not. Considered to be amongst the biggest threats to Apple and Nokia, RIM’s co-CEOs structure has succeeded, but only so far as to please its small target audience with handsets that lack variety. Three years back, RIM’s mcap stood at an all-time high of $73.47 billion (Q2, FY2008). Since then, RIM has lost 84.14% in m-cap and is today, worth only $11.65 billion. In fact, over just the last five months, with delays in the launch of its tablet Playbook (and the poor reviews) the company’s share price has fallen by 65.5%. RIM in Q1, 2011, lost 5.1% of its global market share y-o-y (which fell to 14%). On the other hand, Apple (rise of 3% to 18.7%), Samsung (+6.5%; 10.8%), and even HTC (+4%; 8.9%) grew their respective pies. And the future? Both IDC and Gartner have bad news for RIM, whose market share is forecasted to fall to a lower 13% by 2015. For others, the picture is pretty. Android (43.8%), Apple iOS (19.9%), the Nokiasaviour Windows Phone 7 (20.3%) are set to rise further. So where lies the rub? Industry experts claim that RIM is not making a bad product. It is only that the company is not delivering what customers want to pay for. And this is where the two co-CEOs are finding hard to match their thoughts. Lazaridis would prefer selling something unique and mass-pleasing, while Balsillie does not seem too confident about RIM representing simple technology. A case in point of this company making a product unnecessarily complicated is the Playbook tablet. Why on earth would any user want to link his tablet to his smartphone to even send an email? Again, time is lost, and the worst case scenario is right in front of the world. Smartphones with no innovation, tablets that are not selling for the right reason (at present, what RIM is selling is a half-baked tablet, on which there is no email app, no calendars, no notes app et al), and two co-CEOs whose performance cannot be questioned as they are also the co-Chairmen of the Board of Directors of RIM. Balsillie should step down and perhaps assume the role of the CTO and Laziridis should continueas the sole CEO and not allow geeks to force him to sell engineering feats that do not help win customers’ dollars. What RIM needs to do fast is to make rapid, incremental alterations to its hardware, software, and platform products. If it does not, it only risks giving up the high-end status cult-crown, and will over time, slip in the priority lists of carriers, and witness a constant fall in margins. Remember: Palm was also once a smartphone leader, but is today, almost nowhere on the charts. RIM can become the second Palm. Balsillie cannot even blame any lack in R&D dollars for not getting his products right. Warren Buffett once wrote in one of his book titled, ‘On the Interpretation of Financial Statements’, that, “If a company has to spend more than a certain percentage of its gross profit on R&D, its competitive advantage cannot be sustained...” According to him, that percentage is 15%. RIM spent 15.86% of its gross profits in R&D last year (FY2010-11). See where the problem is? The geek co-CEO is burning cash, while the salesguy co-CEO is only getting complex stones to sell! Summing up the solution, Rick Wartzman, Executive Director of the Drucker Institute at California- based Claremont Graduate University writes in a BusinessWeek article titled, ‘RIM’s Prickly Board Problem’, “Some governance experts have long suggested that a good way to foster the kind of independence Drucker advocated is to have one individual acting only as CEO and another individual acting strictly as Chairman of the board. Indeed, over the past 25 years, the trend toward dividing these jobs has accelerated, so that 40% of S&P 500 companies now follow this practice. With RIM having had trouble launching new products, its profit forecast dwindling, and layoffs mounting, the board needs to demonstrate that it understands management’s performance is nothing to phone home about.” Strange – in case of Apple, the exit of its CEO is considered a danger to the company. In RIM’s case, the opposite is true!

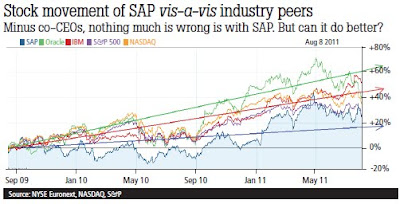

Other creaky seesaws with two co- CEOs promoting organisational paralysis can be seen too. Bill McDermott and JimHagemann Snabe who have been co- CEOs of SAP, since February 7, 2010, have actually been leading the least-attractive outfit in enterprise solutions business for shareholders. Even in a growing enterprise solutions market (especially after recovery started post-2010), since they took charge of SAP, the company has lost 1.93% in m-cap. In fact, during the very next session of trade post announcement that the duo would take charge of SAP, the stock grew slimmer by 5.82%. To make a quick comparison, since Feb 2010, SAP’s competitors, led by single bosses who can hardly be described as consultative or the sharing types, have done better. While tyrant- Larry Elisson’s Oracle produced a return of 13.77% during the past 17 months, the salesguy-Sam Palmisano’s IBM increased his investor’s money by 40.44%!

It was the two co-Chairmen and co- CEOs Michael Klein and Tom Maheras of Citi Markets & Banking (Citi’s investment banking arm) who led the division to becoming the highest contributor to the bank’s total losses of $29.38 billion in FY2008 & 2009. When Anshu Jain was crowned co-Chairman and co-CEO of Germany’s largest bank (Deutsche Bank; alongisde Jurgen Fitschen) the stock market reacted negatively – one trading session after the announcement on Jul 26, 2011, the stock was down 3.31% to $53.77. Nine trading sessions later (Aug 8, 2011), it had shed 21.86% (at $43.41). Why such a stigma attached to co-CEOs? History is proof. Whether it be MySpace’s Jones and Hirschhorn or Wipro’s Paranjpe and Vaswani or Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia’s Millard and Marino, co-CEOs have always failed the litmus test. And quite spectacularly so. Either the company has suffered or they have been replaced (and the company still suffers!). These outcomes are summarised well by a 2010 paper titled, ‘Shared leadership: Is it time for a change’, in which Dr. Michael Kocolowski of South Florida University writes, “We are dealing with a universal myth: in the popular mind, leadership is always singular. A shared leadership issue to consider involves decision making. Since it is sometimes difficult for a more than one leader to reach consensus, decisions can take longer to make. The benefits of complementary leadership are negated when agreement about organisational priorities differ and irreconcilable differences impede decision making and forward progress.”

When the 20-feet long, 2 tonne-weighing Stegosaurus (a dinosaur that lived in the Woodlands of western North America) was first discovered in 1877, scientists were foreign to the idea of living beings with gigantic lizards & walnut-sized brains. Therefore, a palaeontologist named Othniel Marsh put forward his claim that a second brain resided in the Stegosaurus’ backside, which helped him control the back and lower part of its body. Debates continued over this extinct being that walked the Earth, 150 million years ago. But there is one lesson which this Jurassic Park-page has for today’s board of gigantic organisations that fear extinction: the second brain wherever in the body didn’t quite help Stegogaur’s fate? And it doesn’t seem to be working too well in the modern world either. There can be only one emperor to the empire. There should be only one leader in the corporation!

Anti-stimulus

| 21 | and gross investment | -1.2 | 3.7 | 1.0 | -2.8 | -5.9 | -1.1 |

| 22 | 2.8 | 8.8 | 3.2 | -3.0 | -9.4 | 2.2 | |

| 23 | 0.5 | 6.0 | 5.7 | -5.9 | -12.6 | 7.3 | |

| 24 | 7.8 | 14.7 | -1.8 | 3.1 | -2.7 | -7.3 | |

| 25 | -3.9 | 0.4 | -0.5 | -2.7 | -3.4 | -3.4 |

Rabu, 10 Agustus 2011

The Case for Software Patents

"Because of software and process patents any company could be sued for almost anything. It is impossible to know what the next patent to be issued will be and whether or not your company will be at complete risk. It is impossible to go through the entire catalog of patents issued over the last 10, 15, 20 years and determine which will be used to initiate a suit against your company."

I have a ton of respect for many of the people arguing against software patents, but I disagree strongly with their arguments. I think software patents play an important role in encouraging innovation, especially by small companies. The loss of them would make it harder for small companies to survive, and would discourage fundamental innovation in software.

The online debate about software patents is very contentious, and much of it focuses on philosophical issues like the nature of software and whether that's inherently patentable. The debate also often gets mixed with the contention that all software should be free. I'm not going to get into either topic; the arguments are arcane, sometimes quasi-religious in their fervor, and besides they've already been debated to death online.

What I want to focus on is the broader issue of the economic role of patents and how that applies to software. The patent system is designed to encourage innovation by giving a creator a temporary monopoly on the use of an invention. Does that mechanism work in software? What are the problems? And what's the best way to fix them?

When you take that perspective, I think it's clear that there are some genuine problems with software patents. (Actually, there are problems with patents in general, and software is just the most prominent example.) But I think there are better ways than a ban to solve those problems. To me, banning software patents to solve patent problems would be like banning automobiles to stop car theft. The cure is far worse than the disease.

The value of software patents

Let me start with a personal example. As I've mentioned before, I'm working on a startup. When we brief people on what we're doing, one of the first questions we get is, "how will you prevent [Google / Apple / Microsoft / insert hot web company here] from copying you?"

A big part of the answer is, "we've filed for a patent."

A patent isn't magic protection, of course. It might not be granted, and even if it's granted, patents are difficult to enforce against a really big company. But it reassures investors, and more importantly if a Facebook or Google wanted to copy our work, the patent makes it safer and quicker for them to buy our company rather than just ripping us off. So it helps to protect the value of our company.

Without the patent, I think it could be open season on us the moment we announce our product.

Advocates of eliminating software patents say there are other ways to protect software companies. The first is that software can be copyrighted. That's technically true, but the only thing copyright protects you from is word for word theft of your source code; it does not protect inventions. For most software innovations, copyright is no protection at all.

The second argument is that small companies should move quickly, so the big companies can't catch up with them. The idea is that if you move fast enough, you won't need patents. I think there's a consumer web app bias in that advice -- it works best for small apps that can be adopted quickly, or that have a strong social effect (so the user base is part of your competitive protection). It doesn't work well for software tools that have a slower adoption curve. The more complex and powerful the software, the slower the adoption cycle. This is especially true for enterprise tools. Without patents, those companies are exquisitely vulnerable to being ripped off soon after they launch, when they're just starting to gain word of mouth.

So for companies creating new categories of software, and especially for enterprise software tools, I think patents remain the best (and really only) protection from theft.

But what about the damage being caused by abuse of the patent system? If we keep software patents, are we then endorsing those abuses?

I don't think so. In the articles I've seen, there are two primary arguments for eliminating software patents: Trolls and patent warfare. They need to be discussed separately.

Discouraging patent trolls. The troll problem is something we all know about: patent licensing companies buy large collections of patents and then extort fees from companies that had no idea they were violating the patents. That's the core of the problem Mark Cuban was talking about above, and it is outrageous. These surprise lawsuits can have a devastating effect on smaller companies that can't afford to hire a lawyer to defend themselves. Even if you're in the right, it can be so expensive to defend yourself that you just have to give up and pay the license fee. That definitely has a chilling effect on innovation, it is contrary to the intent of the patent system, and therefore it needs to be restrained.

But I think the answer in that case is not to eliminate software patents; it's to restrict the right of "non-practicing entities" (patent trolls) to sue for patent infringement. That would still have a financial effect on small companies -- in the case of my startup, it would make it harder for us to sell our patent if we wanted to. But patent law exists to protect the process of innovation, not to protect inventors for their own sake. If you can't put your patent to good use, you aren't contributing to the public good and you shouldn't get the same level of protection as a company that has built a business around a patent.

Patent warfare is a very different issue. Several large tech companies are using patent lawsuits to slow down competitors and pull revenue out of them. Eliminating software patents would not stop these wars; they're also based on hardware patents, antitrust law, and any other field of law that the companies can apply. It's like one of those cartoon fights in a kitchen where a character opens up a drawer and throws everything inside it.

Yeah, like that.

The underlying problem here isn't about patents; it's about the use (and abuse) of the legal system as a competitive tool. I've had more involvement in tech industry legal wars than I want to think about: I gave depositions in the Apple-Microsoft IP wars, and I testified in Washington in the Microsoft antitrust lawsuit. The overall experience left me plenty cynical about the legal system, but it also persuaded me that big tech companies are perfectly capable of taking care of themselves in court. They do not need our help. You should think of lawsuits as just another way that tech companies express love for one-another.

I'm somewhat sympathetic to the Android vendors being sued by Apple, but a lot of it is their own fault. HTC in particular has no one to blame but itself for its situation, in my opinion. HTC was one of the first companies in mobile computing, creating PDAs for Compaq and early smartphones for Orange and O2. I've got to believe that if HTC had been thinking clearly about patents, there are a lot of fundamental mobile inventions it could have patented. Then it would have had a big enough patent portfolio to force a cross-licensing deal with Apple.

The same thing goes for Google. When it decided to enter the mobile OS business, it should have expected that it would end up at war with Apple and Microsoft (heck, anyone could have predicted that). Google should have bought up a big mobile patent portfolio (like maybe Palm's) back when they were inexpensive.

Are we obligated to change the patent laws just because Google and HTC were careless? No. Is it in the public interest for us to intervene anyway? I doubt it. Here's how the mobile patent wars will play out: The big boys will do a whole bunch more legal maneuvering, they'll scream bloody murder, and in the end one of them will write a check to the other. Then they'll all go back to work.

My advice: If it bothers you, stop reading the news stories about it. Or sit back and enjoy it as theatre. It's hardly an important enough issue to justify stripping the patent protection from every small software company in the US.

A world without software patents

If you want to understand the importance of software patents, go back and talk to the first people who patented software. That's what I did. Two years ago, I corresponded with Martin Goetz, holder of the first software patent (link).

Goetz was a manager at Applied Data Research, one of the first independent app companies in the 1960s. ADR made applications for mainframes, and IBM copied and gave away a version of ADR's Autoflow application (the first commercially marketed third party software app). ADR might have been wiped out, but it had patented Autoflow, and it was able to successfully sue IBM. That lawsuit, plus a related one by the US government, laid the foundations of the independent software industry by forcing IBM to stop giving away free apps for its mainframes.

The lawsuits involved a lot of legal issues, including antitrust, so you can't say that software patents alone led to the birth of the software industry. But I think it's clear that patents helped codify the value of software independent from hardware. If that value hadn't been recognized, the antitrust suit would have been meaningless because there would have been no damages.

So antitrust and patent law have worked together to help protect software innovation. Antitrust helped to restrain big companies from giving away free competitors to an app (although that protection has eroded lately), while patents restrained big companies from copying apps directly. It's like a ladder. If you pull out either leg, I worry that it won't stand.

In his online memoirs (link), Goetz makes the case that application innovation was slow and unresponsive to users in the decade before software patents, and accelerated dramatically in the decade after. I agree. That is exactly the sort of innovation that patent law was meant to encourage, and so I view software patents as a success.

Without software patents, I think it would be far too easy to go back to the bad old days when the big computing companies walked all over small software companies, the software industry consisted of only consultants and custom developers, and software innovation moved at a much slower pace.

_____

More reading: Software entrepreneur and investor Paul Graham wrote a nuanced and detailed take on the subject here. Some of his conclusions differ a bit from mine, but the essay is well worth reading.