Two weeks ago, I asked why mobile application sales are dropping. A great discussion followed, with many different perspectives (if you haven't read the comments, I encourage you to check them out).

To me, one of the most striking comments was the one no one made – nobody came back and said, "you're wrong, sales are actually going well." I think we have a consensus that there's something wrong with sales of sophisticated mobile data apps – native apps that are more than just games or ringtones.

There are two schools of thought on why app sales are down. One perspective is that the market was a mirage in the first place – most people don't care that much about mobile apps, and to the extent that they do, mobile browsing is a good substitute. I think this perspective is growing quickly among industry insiders, and even someone from Microsoft largely seconded it.

Another interesting example of this view is the weblog i-Mode Business Strategy, which tracks adoption of i-Mode data services. It's carrying a lot of quotes from operators and others saying that a mobile device should be focused on a single purpose, and the whole idea of deploying a lot of different apps or functions is low-value.

"All i-mode applications are in fact secondary, the primary being the voice. The secondary applications typically struggle through out their life cycles for the lack of focus and synergy."

The other perspective is that a diverse market for mobile data exists, but we just haven't tackled it correctly yet. For example, Bob Russell at Mobile Read wrote a very kind commentary on my post, but also strongly encouraged people not to panic and give up on the future of mobile data. Several of the other replies to my post echoed that theme.

I'm somewhere in the middle. As I've written before, I believe that a mobile device has to solve a compelling problem before people will buy it. Solving fifteen problems is too hard to market, so there needs to be one flagship function or usage that gets a device sold in the first place. In this respect, I think the "mobile device = appliance" folks are right.

But once the user gets a mobile device, I think many customers will allow it to blossom into more usages – if that blossoming process is handled properly. That's where I think the mobile data world fails today, and that's what I think we need to fix.

The role of mobile data

When I started work at Palm in 1999, I was already using a handheld to track my calendar and contacts, but not much else. I was lucky enough to get a cubicle in the middle of the developer relations team, who taught me all about the third party apps that were just then starting to take off for the platform.

The variety was so huge that I'd spend hours browsing around on PalmGear, picking out new things to download. Many of the applications turned out to be things I tried once and never touched again, but a few filled meaningful roles in my life and I came to depend on them.

There was my buddy Convert-It, which converts between English and Metric measurements (a must for any competitive analyst based in the US).

Tide Tool tells me when it's a good time to go tide pooling at the beach.

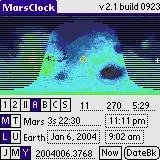

Mars Clock lets me track the time of day on Mars for the Mars Rovers. (Why does that one matter? Because if you're browsing the Mars Rover pictures that NASA posts on the Web every day, Mars Clock lets you convert between the Mars days that NASA lists and actual Earth days – so you can figure out when a picture was taken.)

This is a treasure chest

To me, the Palm Launcher became a treasure chest of useful little software gems, things that enhanced my life and made me happy. But I discovered that my gem collection was different from everyone else's. Tide Tool didn't matter to most people, and Mars Clock was interesting only to the fanatics who followed the photo stream from the Mars Rovers. Other people had their own favorite apps that I didn't care about.

Even among the Palm enthusiasts, there was never a single "killer" application everybody used. Instead, everyone had a different set of personal killer applications that met their own individual needs. Each person was a vertical market of one, the exact opposite of a mass market.

I discovered that when I was talking with potential customers or the press, I could hook almost anyone on Palm if I had fifteen minutes to show them the range of software available. But you can't spend a quarter hour per customer on a product that sells for only a couple of hundred dollars – that's a great way to go broke slowly. So we started to look for mass market ways to have that conversation.

At one point Palm planned an extensive TV advertising campaign for the range of applications, called "The Perfect Day." The first commercial was already finished when the tech bubble burst and Palm's stock value collapsed. The company decided to cut expenses, and the commercials were the first thing to go. The video was shown at a few trade shows, and that was all. (I tried to find a copy of the commercial online, but couldn't. If you know where to see it, please post a link.)

Later, when I was at PalmSource, we didn't have nearly enough money to do TV ads, so we tried to use the Web to spread the story. The result was something called the Expert Guides, a set of about 50 volunteer-written guides to applications for Palm OS. I'm more satisfied by these guides than I am by just about anything else I was involved in at Palm.

If you want to understand the power of mobile data software, and what it can mean to a person's life, browse some of the Guides. The ones on personal health, aviation, and professional medicine are especially impressive, but you can also find quirky things like cigar and liquor software, scuba diving software, and software for various religions.

In addition to creating the Guides, we ran a couple of contests soliciting first person usage stories from users. They were big successes, generating several thousand stories. They ranged from comical to heart-wrenching – people using handhelds to overcome disabilities or start new careers. Almost every story featured different apps. One story I remember in particular was reprinted in the Aviation expert guide:

"I'm a Mission Pilot with the Civil Air Patrol, the auxiliary of the U.S. Air Force. Installed on my Palm Powered device (a Tungsten T now, but over the past six years I've owned an i705, Palm Vx, Palm IIIx and Pilot Professional) are several aviation application including the Airplane Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA) airport directory. It contains virtually all information about thousands of airports across the US. On a January 11 night flight over northeastern Oklahoma, we heard a pilot call over the radio that he was having difficulty finding his destination airport in the darkness. He was alone and his charts were inadequate, out of date or missing. While my crewmember dug through his flight bag of charts, maps, directories and other guides, I pulled my Palm i705 out of my flight suit, turned on its internal light, opened the AOPA eDirectory and found information on the airport that this pilot was flying to. Within 60 seconds, my radio call advised the lost pilot of the airport's location, frequencies, hours of operation and instructions for turning on runway lights and rotating beacon from his aircraft. And my hands never left the flight controls. Is the Palm a great device? You bet. Is there a wide variety of software for use on it? An unbelievable amount. Is it convenient to use, even while flying an airplane? Absolutely. A lifesaver? The other pilot would certainly say so. And it's never farther away than the front pocket of my flight suit."

We had a database with several thousand of those stories. We never figured out what to do with them, other than list a few of the best ones in the Guides.

Based on all this interaction with customers, I an utterly convinced that mobile data, and all the myriad applications associated with it, will eventually be a very common, well-loved part of the lives of huge numbers of people around the world. This stuff is just too useful once you really dig into it.

I'm also convinced that conventional marketing won't make mobile data happen, because the compelling thing about mobile data isn't the total number of applications – it's the individual discovery of an application that does something critical just for you. We have to find a way to explain mobile data differently to every individual person.

After you think about it for a while, the right place – maybe the only place – to explain this is on the device itself. I think the right way to do it would be something like this:

When the user first gets started, the device asks the user a few questions about their work and interests. Based on the user's responses, the device suggests the installation of appropriate software. So, for example, if the user is a doctor and a boy scout troop leader, the device suggests a selection of medical software, and a boy scout troop management program (yes, there's an Expert Guide on that, listing about 70 relevant applications, including knot-tying instructional software -- something critical for a Scout). If the user agrees, these are downloaded to the device, and the user's wireless account is automatically charged for them. If the user doesn't agree, the device makes it easy to come back and buy the software later.

By customizing and automating the whole application shopping process, we make it easy for people to discover what they can do and get used to the idea of using their device for more than one purpose.

I think this integrated discovery and install process is the key to making mobile data take off.

Why hasn't it happened already?

If the right thing to do is so obvious, why hasn't some mobile OS company done it already? I spent the last seven years wondering about that question, and never got a satisfactory answer.

But I get it now.

Making real, personalized mobile data succeed isn't in the critical interest of any of the powers in the mobile design chain.

Hardware vendors focus on the lead solution that's built into their device, because that's what drives the hardware sale. So, for example, Palm has a strong incentive to spend all its time making e-mail on the Treo work great.

The OS vendors focus on the needs of the people who control their sales. That means supporting the feature requirements of the mobile operators, because they're the ones who decide if devices with a particular OS will be offered to users.

To an OS company, the operators are a feature requirements black hole, an "endless aching need" in the words of Bette Midler and Amanda McBroom. There's always one more feature they want implemented, or one more deal you can close if you just respond to a request. These opportunities expand to consume all available engineering resources, no matter how many engineers your company has.

I finally understood this a couple of months ago when I was talking with a former Palm employee who had moved on to one of the biggest mobile-related companies – a firm so huge that you'd assume they have enough engineers to do anything. We were talking about flaws in the user interface of a new product the company had released.

"Hey," I said to my friend, "You're on the inside now. Why don't you just call the product manager and explain to him what's wrong?"

"I did," my friend replied. "But the product manager said all the engineers are busy answering operator requests, and there's no one left to work on user features."

"There's no one left to work on user features." If mobile data fails, you can carve that on the tombstone.

We need a new platform – sort of

If we can't count on the OS companies to make mobile data work, then the obvious answer is to get away from the OS companies. Separate applications discovery, purchase, and compatibility from the underlying OS. Let the OS company serve the needs of the hardware companies and operators, while this new software layer serves developers and users.

What we need isn't a new OS, we need a new software layer on top of the OS.

I think that software layer should include:

--The APIs needed to run the applications, consistent across all devices so developers can write once and run anywhere (think of this as Java done right). That creates the largest possible market, encouraging the creation of the focused vertical applications that drive mobile data adoption.

--The software discovery and sales experience. The whole chain from learning to purchase to billing to installation should be built in, to make it effortlessly easy for people to try and install new mobile apps.

--The billing system needs to be managed carefully. The right thing is take a sustainable, restrained cut of developers' revenue and grow along with them. Many online mobile software stores take an enormous cut of the developer's revenue. That doesn't cultivate a developer community, it's more like running a McCormick harvester across it – you bring in an impressive harvest for a little while, but in your wake you leave an empty field of stubble.

--An open garden. Any developer should be free to add an application to the store. Real mobile data is so diverse that no entity on this earth is capable of determining in advance what people will want. Rather than trying to pick winners, the platform vendor should take a uniform cut from everyone and let Charles Darwin choose the winners. Better yet, put in a user rating system to help the best apps rise to the top.

--Sandboxing. Because anyone can publish an app, the software layer should be thoroughly sandboxed so that a rogue app can't mess with the phone network. This is much easier to do when the layer is built on top of the OS rather than within it.

--The layer should include enough of the user interface so that developers don't have to rewrite their apps for every different device.

Which companies could make it happen?

No one's putting together the whole offering yet, but there are some promising possibilities...

Adobe Apollo. Adobe says it's creating a software layer that will run on top of both PCs and mobile devices. Adobe has enough financial resources to make the necessary investments, and operators are anxious enough to get Flash content that they might agree to bundle Adobe's software.

But to succeed, Adobe would need to give away Apollo. Today the company is charging for Flash in the mobile world, which will limit its deployment and prevent the creation of a standard. Also, Adobe hasn't shown any signs of including application discovery or purchase in Apollo.

Microsoft WPF. Microsoft is working on a software layer that's conceptually similar to Apollo, called Windows Presentation Foundation. Like Apollo, it's not clear if WPF will include the software discovery and purchase experience. Also, Microsoft is holding some features out of the cross-platform version of WPF in order to prevent it from cannibalizing native Windows sales. That's a very difficult line to walk.

Nokia S60. Nokia's S60 software is closely tied to Symbian, but the company could theoretically separate it and offer it as a layer. I have no idea if that has been considered, or how hard it would be to implement. Nokia has been making some efforts at improving the app discovery experience, including the recent announcement of the "Nokia Content Discoverer," one of the most awkwardly-named software products I've heard of in the last five years. I like the idea, though – it's supposed to help people find content and apps. I haven't been able to find any pictures or video of the product in action. If you're aware of any, please post a link in the comments below.

Nokia's other handicap is that it's very closely tied to the operators. It would have to hive off resources to support the apps platform separately from operator influence.

StyleTap. This small Canadian company has created a Palm OS emulator and is selling it for use on Windows Mobile devices. So you can run most Palm OS apps on Windows Mobile. There's no software discovery element, but it is a nice software layer, and could be evolved into a layer for all mobile devices. Unfortunately, StyleTap is charging $30 a pop for the emulator. If they wanted to become the mobile software layer of the future, they'd need to give it away and make money through app sales. I doubt a company of their size can afford to do that.

Brew. Qualcomm's Brew has one of the nicest software downloading and billing infrastructures I've seen, and includes a set of APIs. So it's a full software layer. Its two problems are first that it's made by Qualcomm, a company that already holds – and charges for – many fundamental mobile patents. The last thing mobile companies want to do is give Qualcomm more control over their lives. The second problem is that Brew is set up as a series of closed gardens. The operators choose which apps to offer, and there's no discovery experience that I'm aware of. So I'd classify Brew as great technology hamstrung by a completely wrongheaded business model.

Savaje. This company has gone through a full cycle of being unknown, hyped into extreme prominence, and then dropped back into obscurity. What they're trying to do is fix Java, by making it consistent across devices, efficient, and wrapping a better business and technical infrastructure around it. The question about Savaje has always been whether or not they can deliver. I'm not close enough to them to judge that, but if they get their act together they could be a promising option.

I know I've skipped a lot of other candidates, but hopefully you get the idea (if I missed your favorite, feel free to post a comment about them). There are a lot of companies trying to make various sorts of software layers, but most of them are focusing on the APIs and technologies, the traditional control point in the PC world. That's nice, but what's really needed is a new business layer and infrastructure, not just another set of APIs. I think the first company that realizes this will be the one that drives the blossoming of mobile data.

I hope it'll happen soon.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar