Three mobile-related news items caught my eye today.

Welcome to the real world

The first item was the least important. Skype CEO Niklas Zennstrom talked about getting his software on mobile phones:

"When we began developing the mobile-phone version, we didn't realize the number of technical obstacles. It is challenging and is taking much longer than expected."

Well, duh. There are a couple of ways you could use Skype on a mobile phone. One is to establish an data connection via 3G and then use the data channel to make a call. The operators tend to be a tad wary of that because it basically cuts off most of their revenue.

Then there are WiFi phones. The difficulties there include dreadfully short standby battery life (because 802.11 uses much more power to maintain presence than a cellular network does) and endless difficulties handing off a call seamlessly between a WiFi network and a cellular network. (Someone in the industry once told me confidently that the solution is to pre-emptively establish a connection to the cellular network anytime the user gets close to the edge of the WiFi network. Problem: you're almost always at the edge of the WiFi network unless you're sitting on the transmitter. So basically your phone will almost always be making two calls at once.) Pairing to the diversity of WiFi base stations out there is also a lot tougher than many people realize. Plus many of the operators don't want mixed WiFi/mobile devices to succeed because they weaken the operators' control.

Oh, and the first WiFi phones are butt-ugly.

The tech industry is excited about WiFi mobile phones because it wants somebody to make the operators disappear. I'm fine with that, and I like Skype (I'm a user). But you've got to differentiate between the technologies you want to be real and the ones that actually are.

My guess is that, especially in the US, we'll see WiFi phones sell in volume first as cordless phones in the home, where you don't expect to roam and a lot of people already have WiFi base stations. I could maybe picture them on college campuses, which often have very broad WiFi networks and a lot of students anxious to make cheap calls. In Europe, there is more possibility for dual cellular/WiFi phones because they can be sold aftermarket, bypassing the operators. But you still have to deal with the handoff and pairing issues.

If you want to replace a mobile phone for the mass market, you have to come pretty close to the usability and mobility of today's mobile phones. That will be very, very, very hard to achieve with WiFi.

Tragic but not surprising

I'm seeing almost no coverage of this in the US tech press, but Benq announced that it's closing down the mobile phone business that it acquired from Siemens, just one year and 29 days after the deal closed. At the time of the deal, the combined companies were the fourth largest mobile phone company in the world.

Siemens once had huge ambitions in mobile phones, but it never seemed to find a clear market identity. It was one of the few mobile phone companies to license Series 60 from Nokia (a disaster), and it launched a very aggressive campaign to create a line of fashion designer phones (another disaster).

Outside of Germany (where the Siemens brand is very well respected) the company was mostly known as a supplier of low-cost mobile phones. When Nokia decided to take back market share by leveraging its high production volumes to cut prices, Siemens went into a death spiral from which it never recovered. The mobile phone unit was already in deep financial trouble when Siemens sold it, and in fact they basically paid Benq 250 million euros to take the business off their hands. (Benq had to assume some of the contract liabilities to Siemens' German work force, and supposedly agreed not to do layoffs in the Siemens mobile phone business for one year.)

Apparently the Siemens mobile business continued to decline in the year after the deal, and the press release from Benq was amazingly blunt:

"Both revenue and margin development will fall far short of expectations in the important Christmas quarter. [Mike's translation: The operators refuse to sell our stuff; that's how we know in September that we're going to have a bad Christmas]. Due to the discontinuation of further financial support from the parent company, BenQ [Translation: We have thrown too much money into this thing already], and the resulting lack of liquidity and implicated disruption to business [our mobile division is flat out of cash], BenQ Mobile in Germany will file for insolvency at the local court in Munich within the next few days [We're laying off everyone, selling the buildings they work in, and stiffing as many creditors as we can. But we'll keep using the Siemens-Benq brand for another four years, because we get to do that under the terms of our deal.]"

The situation is sad for the former Siemens employees, and sad for Benq's ambitions. A year ago the phone ODMs (manufacturers who don't sell under their own names) were supposedly about to turn themselves into the masters of the mobile phone industry, with Benq leading the way. Now Nokia, SonyEricsson, and Motorola are all on the rebound.

I'll close with comments by Richard Windsor, a very brainy investment analyst with Nomura in London:

"BenQ has effectively signalled the end of its mobile phone business.... Handset delays, testing and acceptance problems have prevented devices getting to market on time which has proved catastrophic for revenues, profits and cash flow.... There can be little doubt that this is the end of the road for BenQ's ambitions to become a branded handset manufacturer.... We expect that Nokia will get the lion's share of BenQ's business as BenQ has remained mostly in the low end where Nokia is by far the strongest.... Negative for Symbian as yet another licensee appears to have gone up in smoke, dealing its credibility as an impendent software vendor a blow. Negative for the Linux consortium as BenQ's long-term feature phone roadmap looked like it was heading towards Linux and the consortium is now deprived of a credible member."

Not sure if it's tragic, but it's ominous

The other sad but not surprising end was the abrupt discontinuation of Mobile ESPN, the MVNO focused on sports fans. (An MVNO is a mobile phone operator that buys air time from one of the big operators, pairs it with specialized phones and services, and sells the bundle to the public.) I thought Mobile ESPN's phone interface had huge flaws, but most observers are attributing the failure to bad marketing or just a general failure of the MVNO concept.

A lot of nasty rumors had been circulating about Mobile ESPN, which is why the shutdown was not surprising. At CTIA earlier this month I spoke with one well-connected industry insider who was furious about the situation. He said it's unreasonable to expect a new MVNO to find its market immediately.

He had a point. I strongly believe in the idea of MVNOs, because they enable an operator to focus on vertical solutions for vertical markets, which is the way most mobile data usage will develop. I think Mobile ESPN was poorly implemented. But other MVNOs are more promising (Helio remains my favorite example). I hope they'll be given enough time to prove themselves.

A year ago MVNOs were supposed to be the next big thing in the operator world. Now many people are trashing them. This is typical of the faddish, short-term behavior of the mobile industry. When you have no vision of your own, you jump on whatever idea is trendy at the moment. MMS. WAP. And now MVNOs. The industry often behaves like a flock of birds – it doesn't really matter where you go, as long as you don't get separated from the others.

I wrote an article for the newsletter of my employer, Rubicon Consulting. Thought it might be of interest to some folks here.

This will probably sound crazy, but despite all the hype about Web 2.0 and web startups, the most common mistake we see tech companies making with regard to the web is underestimating its long-term impact on their businesses...

Click here for the full article.

==========

By the way, I owe thank-yous to the last two Carnival of the Mobilists hosts:

Mobile Gadgeteer has some interesting coverage of CTIA, several other cool articles, and also named my article on the RIM Pearl the post of the week. Thanks, Matt!

And the carnival at Mobile Crunch, from the week before, had some CTIA coverage plus a lot of other interesting articles. Sorry I missed linking to you last week, Oliver.

For me, the highlight of fall CTIA this year was that I finally got to play with a Pearl, RIM's latest smartphone. It has more media features, plus a miniscule trackball above the keypad for navigation. The trackball is about the size of a pea, and at first glance I thought it would be too small to be usable. But I was very surprised when I tried it. The trackball works very well. It's fast, so you can zip up, down, and sideways very quickly by sliding your thumb. But it doesn't feel loose or out of control. To select something, you click in on the trackball, which was also more intuitive than I expected. When the interface is structured properly, you get into a nice rhythm of roll, click, roll, all without taking your thumb off the trackball.

I especially liked using the trackball for tasks like setting up an appointment. RIM's thumbwheel-optimized interface translates well to the trackball in this case. The program lists a series of variables (start time, end time, date, etc). You navigate up and down this list by rolling the trackball, click to select an item you want to change, and then roll up or down (or sideways) to make the numbers go up and down. It's extremely intuitive, and you can enter complex information pretty darned quickly.

(I'd love to see a music player with a trackball to navigate the playlists. If the software was structured properly, I think it would be easier and more intuitive than the iPod.)

Browsing with the trackball was uncomfortable, largely because the browser didn't show any signs of being reworked for the trackball. I think browsing works best when you have an onscreen pointer that lets you click on things, and the trackball would be ideal for this. But RIM hasn't implemented a pointer in its browser – instead you just move from selection point to point serially, the same as you would with a rocker or a thumbwheel. This was a disappointing missed opportunity.

Lesson to hardware manufacturers – the user interface and pointing device need to be designed together. An interface that's easy for one pointing device is often uncomfortable for another.

The other part of browsing that I hated was entering URL's using RIM's special QWERTY keypad. If you haven't seen this keypad, it arranges the letters in QWERTY format, with two or three letters per key, so the phone can be the width of a regular mobile phone. As you press the keys, the phone is supposed to decode what you're trying to write. This works okay for commonly used words, but stinks for URLs because they are unfamiliar. Also, the keys are so tiny and flat that it was hard to hit them accurately with my big thumbs.

I finally got frustrated and put the phone in multitap mode (where you press twice for the second letter).

I've heard that with training the recognition gets better, and you get used to using the keyboard. Maybe – Graffiti on Palm had a learning curve too, and millions of people put up with that.

I'm also skeptical about the Pearl's market focus. It's being marketed as a media + email phone, for people who want both RIM-powered email and multimedia entertainment. RIM's core users are mid-career business professionals, and I'm not sure how many of them want to be entertained by their phones. Meanwhile, the people who most want mobile entertainment -- those under age 25 -- are not all that interested in professional e-mail. It's hard to picture an entertainment-focused MVNO like Helio marketing the Pearl. Especially since Pearl doesn't have 3G support.

But multimedia aside, the saving grace of the Pearl is its size. It's both lightweight (3.1 ounces / 88 grams) and thin (.57 inches / 14.5mm). That's .1 inches / 3mm thicker than a Moto Slvr, but it's much thinner and lighter than any previous RIM device. I think it's the first RIM product that looks at first glance just like a modern cellphone. If RIM marketed it as a thinner RIM device, and updated the software to take advantage of the trackball, I think it would be a winner.

Because of the multimedia emphasis and the unmodified software, I'm not sure how well the phone will sell. But I really hope we haven't seen the last of the trackball in mobile devices. It's a substantial improvement.

I went to two conferences this week: the CTIA telephony conference in Los Angeles and The Future of Web Apps in San Francisco. It's always interesting to travel between the Bay Area and southern California. This is going to irritate Bay Area partisans who like to look down on LA, but I think the cultures are almost identical in the two areas. The main difference is that drivers on the freeway in southern California are more likely to yield the lane when you put on your turn signal (the standard behavior in the Bay Area is to speed up to protect your turf).

There are huge economic differences between north and south, though. Los Angeles and the sprawl around it make up an intensely vibrant, wildly diversified economy. No industry dominates. The place is a huge cultural melting pot, and many fashion and social trends incubate there first before they spread around the world.

By contrast, the Bay Area, and especially Silicon Valley, is more like a hothouse full of orchids. There's less diversity, and the atmosphere is a little more inward-focused, a half-step out of sync with the rest of the world.

The vibrancy of Los Angeles outside the Convention Center made a striking contrast to the sleepy atmosphere inside at CTIA. There were very few new products on display, and I didn't see anything that generated intense excitement (the biggest crowd of the day turned out for a stunt bike exhibit). Even the press coverage from the show focused heavily on business worries -- the failure of mobile video to take off, lack of profitability in mobile games, and speculation about mobile advertising.

Later in the week, a two-day conference on web apps was held in the Palace of Fine Arts in San Francisco. The Palace is Greco-Roman fantasy temple left over from the San Francisco world's fair of a hundred years ago, and it's across the street from the newly-built headquarters of the Lucas film empire (where you can see a life-size bronze statue of Yoda). It's hard to picture a more fairy-tale setting for a conference.

And yet, the presentations inside were sizzling with energy. We heard from companies that are creating important new businesses and making meaningful differences in the lives of millions of users – organizations like Flickr, Digg, and Dogster. Silicon Valley may indeed be a hothouse, but it's turning out some very promising orchids right now.

There's a collision coming between the wireless world and the web, and I think it won't be pretty. The best way to describe it is by analogy. Picture a raging river fed by the meltwater of a hundred glaciers. The jagged river valley is suddenly blocked by a dam. What happens?

The water starts to rise, of course. If the dam is well operated, the water can be harnessed to generate power. But if the spillway stays closed, the water will eventually pour over the top of the dam and rip it apart.

The river is the torrent of innovation happening in web apps right now. The dam is the carriers who won't allow that innovation to run freely on their networks. They haven't figured out how to set up spillways and generators, let along operate them, so the pressure of the water keeps growing as web innovation gets further and further in front of what you can do on the wireless networks.

At some point one of the carriers is going to give in, or a technological change will give the web apps crowd unrestricted access to a mobile wireless platform with broad coverage. When that happens, I think the pent up innovation and new business models in the web will sweep through the wireless world like a flood. The longer the pressure builds up, the faster the change will be when it happens – and the more likely that many of the major carriers will be swept aside in the process.

I know this is a very broad and vague-sounding prediction, and if you're confused or skeptical I don't blame you. Next week I'll write in more detail about both shows, to give you the details on what I mean and why I'm saying it.

__________

Thanks very much to David Beers at Software Everywhere for naming my post on European and American mobile phone use the post of the week in the latest Carnival of the Mobilists. There's a lot of interesting material in this week's Carnival.

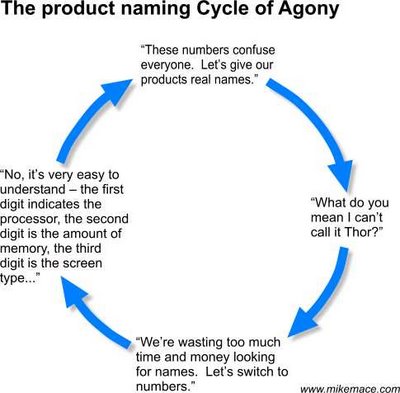

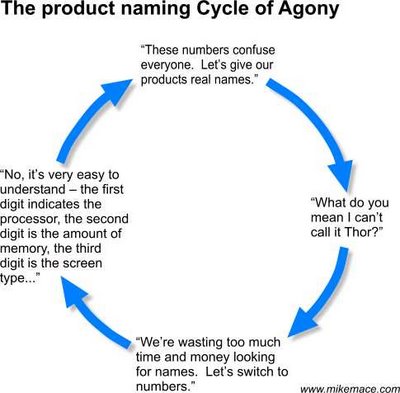

By now you've probably seen the news that Nokia is going to start naming its phones just like the Razr, rather than assigning them numbers.

I'm tempted to make an unkind comment about Nokia once again playing catch-up to others in the industry – first camera phones, then flip phones (or clamshells, as some parts of the world call them), then ultra-thin phones, and now named phones. There's a pattern here, and it's not very comfortable for a company that wants to be seen as a market leader.

But actually I sympathize with Nokia's situation, and I think they are making a noble effort in this case. I also think it won't be fully successful, and I'd like to explain why.

In many years of work at various tech companies, I've been through dozens of naming exercises. Every company that has half a brain somewhere in its marketing department wants to use real names for its products rather than numbers. Names are easier to communicate, and easier for customers to remember. A good name will also have some emotional resonance to it, meaning you need to spend less money marketing it.

But there are several huge problems with using real words as product names.

First, most of the good names are already taken. The situation is a lot like trying to find an interesting and unique URL for a website. Years ago, companies grabbed virtually every interesting name, and a lot of the ugly ones too. When I was at Apple, for example, we tried to secure rights to the names of every prominent variety of apple. Fuji was already taken by the Japanese film company, but we bagged several others. Pippin was one of the big prizes. Because it sounded cute, and we saved it for years before finally blowing it on a multimedia console.

When a company looks for a product name, typically what you'll do is brainstorm a couple of dozen possible names that sound right and maybe have some sort of link to the way you want the product to be perceived. There are always a couple of favorites on the list, and the rest are backups. You then turn the list over to the lawyers to check for conflicts with existing trademarks. When the list comes back a couple of weeks later, the lawyers have inevitably crossed off all the names you liked and also most of the ones you were lukewarm about. Of the four that are left, two will turn out to be either unpronounceable or pornographic in Japanese. You end up looking at the two remaining possibilities and trying to convince yourself that you can live with something that made you want to puke a couple of weeks ago.

This is how one version of Palm OS ended up with the name "Garnet," by the way.

After going through this process a few times, you realize that you're spending far too much money and time on lawyers and naming consultants. So you decide it would be much more convenient and efficient to use numbers or letters instead. You come up with a clever numbering and lettering scheme. Maybe you name your product after the year in which it's released (Windows 95). Or you come up with a clever letter scheme using macho letters like "x," "z," and "f" (Macintosh IIfx). You spend a lot of time explaining the new scheme to the press and customers.

Even though this reduces your trademark search fees, there are still problems to watch out for. Different cultures are afraid of different numbers. In much of Europe and the US, the number 13 is not welcome. You'll terrify some Christians if you use three sixes in a product name, because they see that as the sign of the devil. In Japan and China, the word for "4" sounds a lot like the word for "death," so you can't use that (supposedly, the fear is so strong that the death rate in Asia is higher on days that have a four in them). Is it the fear that's killing people, or does the number itself do them in? Hard to say for sure. If you check out Nokia's product list you'll see that the company is very aware of these issues – there is no four series, there are no products with three sixes in the name, and I could find no 13s at all.

Within 18 months, any numbering and lettering scheme that you choose will start to break down. Maybe you'll still be selling Windows 95 in 1997 and everyone will laugh at you. Or as you come up with new products, you'll have to figure out how to fit them into the existing scheme. You run out of numbers, or have to add more letters to the mix. One day you find yourself trying to explain to a roomful of press people the difference between the 2253xt and the 2253xz. They're all staring at you completely blank-faced, and you wonder why you're wasting your life working on garbage like this. You resolve that the next generation of products will have real names. And the process begins again.

The full cycle from name to numbers and back to names usually takes about six years. Almost every tech company that sells to consumers goes through it. The main exception I'm aware of is Apple. Steve Jobs insists on real names, and is willing to spend what it takes to get them. But he also produces many fewer new products every year than Nokia does.

Motorola was brilliant to use common words with most of the vowels removed from them; you get the image associated with the name, without the trademark fight. But now that's been done, and I doubt Nokia will be able to come up with a similar brainstorm. It produces so many products that it'll be extremely difficult to name all of them, especially if the name searches start to delay product launches. So instead I think Nokia is likely to name families of products, with letters and numbers indicating the actual models. That will work for a while, but some day Nokia will be trying to name a new product family, and the lawyers will report that the only two names they can get clearance for are RinGo and n-Gage. At that point pure numbers will start to look mighty attractive again.

In last week's post about Palm's phone plans, I made a passing comment about the right way to display your mobile phone at dinner in Europe. It turned out to be the most popular part of the post, and produced a couple of requests that I say more comparing European and American attitudes toward mobile phones. I don't pretend to the world's expert on the subject, but I'll summarize what I've seen. Here goes:

In the US, a cellphone is a tool. In Europe, a mobile phone is a lifestyle.

I guess I ought to give a few details. Let me start with a disclaimer: It's very dangerous to talk about "Europeans" as if they're some sort of unified cultural group. Europe is a continent of many nationalities, and each one has a different culture and history. National regulations on phones also differ dramatically within Europe, which has an important impact on mobile use.

I saw a good example of this in the responses to my last post. I said all Europeans put their mobile phones on the table during a meal. I got replies from some countries agreeing with me, and others saying I was completely wrong. It turns out the table thing differs from country to country.

It's only slightly less hazardous to talk about a "typical" American mobile phone user. The culture in the US is more uniform than it is in Europe, but there are profound differences between various market segments. The average 16-year-old in the US views a mobile phone very differently than the average 40-year-old. (Come to think of it, I suspect average 40-year-old mobile users in Berlin and Chicago probably have more in common with each other than either of them have with the 16-year-old.)

Now that I've hedged thoroughly, here are those details:

Vocabulary

The differences start with the words we use to talk about the industry. In Europe, a mobile phone is usually called (in English-speaking countries) a "mobile." As in, "I'll ring your mobile." In the US, mobile phones are most often called "cellphones," and that's sometimes shortened: "I'll call your cell."

The term differs in other European countries, of course (for example, Hermann on Brighthand says the term in Germany is "handy.") I do know that if you say "cellphone" pretty much anywhere in Europe, people will look at you like you're a dork. Found that out the hard way.

Occasionally young people in the US use the term "mobile," but it's not very widespread. I try to use the term "mobile phone" in this website because it's understood on both continents.

There are also differences in the terms used to describe the companies that sell mobile phone services. In the US they are generally called "carriers." But the second easiest way to piss off a European mobile exec is to call his or her company a carrier. They are "operators." As the distinction was explained to me, an operator actively runs a network, while a carrier merely delivers something passively.

(In case you're wondering, the first easiest way to piss off a European mobile exec is to ask how his MMS revenues are doing.)

The operator vs. carrier thing is very confusing in the US, because to most Americans an "operator" is a person who runs a switchboard. The archetypal operator is Ernestine, a character created by actress Lily Tomlin. She snorted annoyingly, was rude, and reveled in her ability to manipulate customers:

"Here at the Phone Company we handle eighty-four billion calls a year. Serving everyone from presidents and kings to scum of the earth. (snort) We realize that every so often you can't get an operator, for no apparent reason your phone goes out of order [snatches plug out of switchboard], or perhaps you get charged for a call you didn't make. We don't care. Watch this [bangs on a switch panel like a cheap piano] just lost Peoria. (snort) You see, this phone system consists of a multibillion-dollar matrix of space-age technology that is so sophisticated, even we can't handle it. But that's your problem, isn't it? Next time you complain about your phone service, why don't you try using two Dixie cups with a string. We don't care. We don't have to. (snort) We're the Phone Company!"

–Ernestine

Some people might say that's a good metaphor for a mobile phone company, but it's hard for an American to understand why any company would want to apply the term to itself.

The mobile phone culture

To me, one of the most pronounced differences between mobile use in the US and Europe is that Europe has a more developed mobile phone culture. There are huge variations in attitude from person to person, but on average, people in Europe expect the mobile to play a more prominent, recognized role in the structure of society, and many people look to the mobile as a central source of new innovations. The belief is almost that the mobile phone has a manifest destiny to subsume everything else. This love affair with the mobile phone is far more common in Europe than it is in America.

You can find a good example of this attitude in an essay about the future, on the website of the Club of Amsterdam, a think tank based in the Netherlands:

"Every machine will be a mobile phone, talking to their owner but mainly to other machines.... In 2020 the world is one big video screen, one big video camera, one big mobile phone.... The mobile will act as a "trust machine". It will be our most important lifestyle instrument. It will probably be decomposed with its core elements scattered all over and inside our body."

People in the US can be just as enthusiastic about mobilizing technology, but they often think in terms of shrinking and mobilizing the PC and Internet, rather than growing the cellphone. In the US, the cellphone is often viewed as a necessary tool rather than something to love. For example, an MIT survey in 2004 found that Americans rated the cellphone number one in the list of inventions they hate but can't live without, edging out the dreaded alarm clock.

If you're still having trouble picturing the difference in attitudes, look at it this way – many people in Europe feel about their mobiles the way that Californians feel about their cars.

Okay? Got it now?

The European love of the mobile phone has several facets to it...

Fashion. To many people in Europe, their mobile phone seems to be a fashion statement. It says something about you, much like your clothing. Americans also care about the look of their phones (just take a look at my daughter's Razr, covered in stick-on jewels and shiny dangling beady things). But in general I don't think Americans identify with the phone as deeply.

It seems much more common for someone in Europe to change phones than it is for someone in the US. All phones in Europe are GSM, and people generally understand that you can pop out your SIM card and pop it into a new phone anytime you want. The mobile is just a skin that you wrap around your phone contract. Major retail chains, like Carphone Warehouse, sell large numbers of mobile phones independent of any operator.

Although you can do the same sort of phone swap in the US if you have a GSM phone, it seems like relatively few people do it, and very few phones are sold outside of the carriers' stores. I'm not sure why. I think awareness of the capability is lower (I'll bet a majority of American GSM users couldn't even find their SIM card). And of course many mobile phone users in the US are on CDMA, forcing them to go through the carrier if they want to switch phones. But also, I think there's just less desire to constantly update your phone in the US, because people don't pay as much attention to it.

Design. This is related to the fashion topic, but it deserves a separate discussion because it's so surprising, at least to me. In most consumer goods, there's an approximate consensus on design between the US and Europe. You can find exceptions, but in general clothing, pop music, cars, and furniture considered to be cool in one continent are admired in the other. In fact, a lot of Americans think of "European design" as automatically stylish. But mobile phone styling and features often polarize people in the US and Europe. In Europe, people generally hate external antennas on a phone. In the US, most people don't notice the antenna, and if they do notice it they may well like it because they assume it'll give better coverage.

Many people in Europe love candybar phones. Most Americans think they look cheap and dislike them. Instead, many Americans love flip phones. I think they feel the flip cover prevents accidental calls, and keeps the screen from getting scratched. Maybe they also feel a bit like Captain Kirk when they flip open the phone.

Many Europeans hate flip phones. I don't know why (although I'll speculate that the flip cover makes it inconvenient to send and receive a lot of SMS messages).

SMS vs. IM. Speaking of SMS, it's vastly more popular in Europe than it is in the US. Some of this difference is generational – young people in the US are much more likely to use SMS, whereas it's extremely rare among older Americans. Some of the difference is also training – most Americans don't have a clue how to enter text on a keypad. But even among young Americans, who do the most texting, I think PC-based instant messaging is still the king, now often tied to webcams.

History helps to explain the difference. The US started with a more PC-centric culture, and then IM was pushed aggressively by AOL in the United States, years before many mobile phones here were SMS-capable. There was no great champion for instant messaging in Europe, and besides PCs with Internet connections were less common there in the early days of IM. So SMS had a lot less competition.

Because of differences in mobile phone billing plans, I'm told that sending an SMS was often much cheaper than making a voice call in Europe. US mobile plans, with their large blocks of monthly minutes, supposedly create less of an incentive to use SMS. (In fact, many American mobile plans don't by default include any pre-paid text messages; you pay separately for each one. There's an amusing television commercial by one of the US mobile carriers showing a father relentlessly pursuing his teenage daughter around town – not to keep her out of trouble with her boyfriend, but to keep her from sending text messages on her phone.)

I did a quick spot check of Orange (UK) and Cingular (US) mobile plan charges, to look at the current price differential between voice and text. The main difference was actually that everything in the UK cost more than it does in the US, perhaps due to the horrific dollar-pound exchange rate. The difference between the US and UK in treatment of text messages was not as dramatic as I expected, but it was there. Today the US and UK both charge more for voice than text, but the plans I looked at in the UK almost all either bundled text messages in the base plan, or had options to get a lot of text messages for free if you spent a certain amount on your voice calls. In the US, text messages were always an option that you had to purchase separately, and there was no opportunity to get free text messages. Basically, you have to plan on spending extra if you want to do texting in the US.

(The details: Using a prepaid plan, Cingular in the US will sell you 900 minutes a month for $60, but you'll have to pay $5 extra per month to get 200 text messages. That same $60 spent with Orange in the UK will get you just 325 voice minutes, but 150 text messages are included in the base price. The UK plan creates a strong incentive to substitute text for a voice call when you can.

(If you look at pay as you go plans, Orange charges 38-76 cents a minute for voice calls [depending on whether the call is to a mobile or a land line], and 19 cents for each text message. So a text message is half to a quarter the price of a voice call. However, Orange also gives you 1,000 free text messages if you spend more than $19 a month. Most people would end up getting the free texting, so their effective price for text messaging drops to almost zero. Cingular charges you about 25 cents a minute for voice calls, and five cents per text message. Texting is one fifth the price of a voice call, actually a better ratio than Orange. However, there's no option to get free text messages, so you know you're paying for them no matter what.)

Differences in market structure

Operator power. In general, the US carriers have more power over their customers than the European operators do, for several reasons. The first is that pay as you go plans are much more popular in Europe than they are in the US. In some countries (Italy, for example), almost everyone was on pay as you go the last time I checked. In other places in Europe, users are split between pay as you go and contracts. But I don't know of any place in Europe where as many people are on contracts as they are in the US (please speak up if I've got that wrong – it's hard to find numbers on the percent of users on each type of payment program).

The second difference is mobile phone number portability (which lets you keep your number if you switch mobile operators). Many countries in Europe had it years before it came into the United States. For example, the UK got portability in 1998, Spain and Sweden in 2000, and Italy in 2001. Americans didn't get it until the end of 2003.

Another important difference is that in parts of Europe phone subsidies are illegal. I know about this one because at Palm I used to track the sales prices of mobile phones, and they varied wildly from country to country. I finally figured out that the subsidies were skewing the numbers. The subsidy laws are changing, and they may be allowed in most countries by now.

I think the relatively weaker customer control of European operators has driven faster innovation in Europe, because the operators have to do more to attract customers. They also can't lock a phone vendor out of the market completely, the way the US carriers have been strangling SonyEricsson.

Mobile versus fixed. Fixed-line phone companies in Europe are often monopolies, legendary for high costs and poor service. I have been told by many friends in Europe that it was faster and cheaper to get a mobile phone there than to wait for a land line, which drove very rapid movement toward mobiles. In the US, land line phone service is generally reliable, quick to install, and cheap, so there's much less incentive to get away from it. Some younger people in the US are starting to get rid of their land lines, but the movement is much slower than in Europe.

Reliability of coverage. In much of Europe, mobile phone coverage is more or less ubiquitous. There are always exceptions, of course, but generally you can make a voice call anytime you want to.

This really came home to me recently when I had the good fortune of taking a driving vacation in the fjords of western Norway. That's some of the most mountainous landscape in Europe, but I never noticed a spot where I was out of coverage (check out this coverage map). Contrast that to a driving vacation in the western US, where once you get out of the cities it is almost impossible to get a signal anywhere. For example, when I was in Grand Canyon National Park in Arizona a couple of years ago, I couldn't get a mobile phone signal anywhere in the park.

The usual American excuse for its poor coverage is that US population densities are low. That doesn't hold up to close examination – Norway has about 15 people per square kilometer, the same density as Arizona, which is not exactly crowded. The US overall has about 33, more than double Norway's density. I think Europe is just more dedicated to universal mobile coverage.

Brands. The prominence of mobile phone brands varies tremendously from continent to continent, and even from country to country in Europe. In general, Nokia is much better known and respected in Europe. Motorola is much better known and respected in the US (although it doesn't have the rock star status that Nokia has in Europe). And there are national champions like Siemens, which is heavily respected in Germany but nowhere else I know of. Samsung's brand awareness has been steadily rising in both the US and Europe, and LG is trying to tail along after it.

The differences over Nokia are the most surprising to my friends in Europe. Throughout Europe, and actually most of the world, Nokia is one of the top elite brands, like Nike in sports or Microsoft in computers. It produces an immediate aura of respectability. In the US, Nokia is lost in the crowd of semi-anonymous Euro-brands -- names like Saab or Peugeot that you've heard of but have never experienced personally.

I think Nokia recently compounded this problem with its "It's your life in there" television commercials in the US. The commercial that stuck in my mind was about "Jill," who praises the phone's ability to delete an ex-boyfriend from her phone's address book:

"It is so great because when you go to the phone and you delete and your phone asks 'Are you sure?' You look at your phone and you're like, 'oh yeah, I'm sure.'"

She then gives one of the most annoying, braying laughs I've heard on TV since...well. Ernestine.

I understand what Nokia was trying to do – it was making a sophisticated effort to tap into the mobile phone culture in the US. You can read a detailed ethnographic analysis of the ad campaign here. The problem for me was that, first, the mobile phone culture Nokia's trying to tap into is pretty weak in the US; and second, that Jill has just a whiff of trailer trash about her.

(Nokia has pulled the website for the campaign, which perhaps tells you how well it was received, but you can still find the commercial on the site of the agency that created it. Just follow this link and move your mouse around on the slider at the bottom of the page until you find Jill. You can also check out the other losers Nokia featured in the series.)

Americans tend to respond best to aspirational ads that make them feel good about themselves for buying a product. So buying a Mac will give you kinship with Einstein and Gandhi, which is outrageous but Steve Jobs can pull that off. Nokia's unintended message was that a Nokia phone will turn you into "a sniveling Sex in the City wannabe," as Gizmodo put it.

I think this is typical of Nokia's inability to connect with the American public.

What about the rest of the world?

There are even bigger variations in the mobile market in other parts of the world, but I didn't have the time (or the knowledge) to discuss all of them here. Mobile phone services and features in Japan and Korea make both Americans and Europeans look like techno-hicks. In Japan, the operators have so much power that phones are sold virtually unbranded, and Japanese phone manufacturers struggle to operate anywhere else in the world because the required reflexes are so different. It will be interesting to see what happens in Japan when number portability is implemented there, in late October. Surveys have said that large numbers of Japanese mobile phone users, especially those on Vodafone, would switch operators if the could.

The market worldwide is so complex that I think it's impossible for any one person to understand it all. So please help me out -- if I missed your country, or if you'd like to add to or correct something I said above, please post a comment.

________

Thanks to Steve at 3-Lib for including my post from last week in the latest Carnival of the Mobilists. Check it out here for a collection of some of the week's best writing about the mobile industry.