I'm tempted to make an unkind comment about Nokia once again playing catch-up to others in the industry – first camera phones, then flip phones (or clamshells, as some parts of the world call them), then ultra-thin phones, and now named phones. There's a pattern here, and it's not very comfortable for a company that wants to be seen as a market leader.

But actually I sympathize with Nokia's situation, and I think they are making a noble effort in this case. I also think it won't be fully successful, and I'd like to explain why.

In many years of work at various tech companies, I've been through dozens of naming exercises. Every company that has half a brain somewhere in its marketing department wants to use real names for its products rather than numbers. Names are easier to communicate, and easier for customers to remember. A good name will also have some emotional resonance to it, meaning you need to spend less money marketing it.

But there are several huge problems with using real words as product names.

First, most of the good names are already taken. The situation is a lot like trying to find an interesting and unique URL for a website. Years ago, companies grabbed virtually every interesting name, and a lot of the ugly ones too. When I was at Apple, for example, we tried to secure rights to the names of every prominent variety of apple. Fuji was already taken by the Japanese film company, but we bagged several others. Pippin was one of the big prizes. Because it sounded cute, and we saved it for years before finally blowing it on a multimedia console.

When a company looks for a product name, typically what you'll do is brainstorm a couple of dozen possible names that sound right and maybe have some sort of link to the way you want the product to be perceived. There are always a couple of favorites on the list, and the rest are backups. You then turn the list over to the lawyers to check for conflicts with existing trademarks. When the list comes back a couple of weeks later, the lawyers have inevitably crossed off all the names you liked and also most of the ones you were lukewarm about. Of the four that are left, two will turn out to be either unpronounceable or pornographic in Japanese. You end up looking at the two remaining possibilities and trying to convince yourself that you can live with something that made you want to puke a couple of weeks ago.

This is how one version of Palm OS ended up with the name "Garnet," by the way.

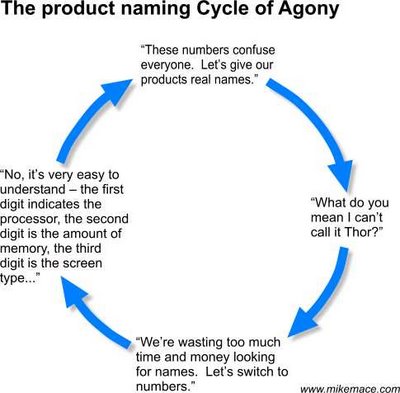

After going through this process a few times, you realize that you're spending far too much money and time on lawyers and naming consultants. So you decide it would be much more convenient and efficient to use numbers or letters instead. You come up with a clever numbering and lettering scheme. Maybe you name your product after the year in which it's released (Windows 95). Or you come up with a clever letter scheme using macho letters like "x," "z," and "f" (Macintosh IIfx). You spend a lot of time explaining the new scheme to the press and customers.

Even though this reduces your trademark search fees, there are still problems to watch out for. Different cultures are afraid of different numbers. In much of Europe and the US, the number 13 is not welcome. You'll terrify some Christians if you use three sixes in a product name, because they see that as the sign of the devil. In Japan and China, the word for "4" sounds a lot like the word for "death," so you can't use that (supposedly, the fear is so strong that the death rate in Asia is higher on days that have a four in them). Is it the fear that's killing people, or does the number itself do them in? Hard to say for sure. If you check out Nokia's product list you'll see that the company is very aware of these issues – there is no four series, there are no products with three sixes in the name, and I could find no 13s at all.

Within 18 months, any numbering and lettering scheme that you choose will start to break down. Maybe you'll still be selling Windows 95 in 1997 and everyone will laugh at you. Or as you come up with new products, you'll have to figure out how to fit them into the existing scheme. You run out of numbers, or have to add more letters to the mix. One day you find yourself trying to explain to a roomful of press people the difference between the 2253xt and the 2253xz. They're all staring at you completely blank-faced, and you wonder why you're wasting your life working on garbage like this. You resolve that the next generation of products will have real names. And the process begins again.

The full cycle from name to numbers and back to names usually takes about six years. Almost every tech company that sells to consumers goes through it. The main exception I'm aware of is Apple. Steve Jobs insists on real names, and is willing to spend what it takes to get them. But he also produces many fewer new products every year than Nokia does.

Motorola was brilliant to use common words with most of the vowels removed from them; you get the image associated with the name, without the trademark fight. But now that's been done, and I doubt Nokia will be able to come up with a similar brainstorm. It produces so many products that it'll be extremely difficult to name all of them, especially if the name searches start to delay product launches. So instead I think Nokia is likely to name families of products, with letters and numbers indicating the actual models. That will work for a while, but some day Nokia will be trying to name a new product family, and the lawyers will report that the only two names they can get clearance for are RinGo and n-Gage. At that point pure numbers will start to look mighty attractive again.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar