IT’S AN OFT-ASKED QUESTION. GUESS WHAT, I DECIDED TO ANSWER IT AGAIN. HOW MUCH SHOULD CEOS BE PAID? DO THE HIGHEST-EARNING CEOS DELIVER THE HIGHEST RETURNS TO SHAREHOLDERS? HERE’S A DUMMY’S GUIDE TO WHETHER THE BOARD SHOULD PROMISE FAT PAYCHECKS TO THE TOP MAN OR NOT.Petty scandals are found aplenty in rich nations. It is no different in business; the synonymity is ironically nostalgic. The correlation is much the same with big scandals too. And much like activists raise their voices against one such prevalent scandal in politics – the fat perks doled out to politicians – there is a group that feels no different about CEOs of multi-billion corporations. They are right. Despite criticism about lack of corporate governance for years, by large, CEOs are swept into offices with a seven to eight figure sign-up membership. Only problem is – before their disappointing terms are over, the boardrooms are filled with the noise of who “could” be presiding over the next company dinner. The failed CEO departs, having stripped shareholders to the bone, and having collected millions (or billions) in fat paychecks & belly-bloating perks!

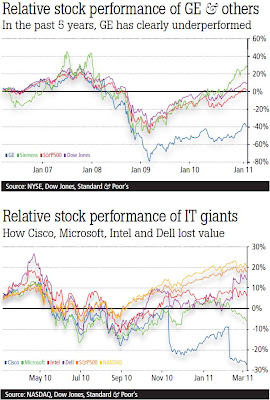

There are many names which surface in this debate of a mismatch between executive compensation and performance in the modern world. The fourth largest US corporation (in terms of revenues for 2009), General Electric, is one. When Jeffrey Immelt took over as CEO on September 7, 2001, everyone was hopeful. He was handpicked by Jack Welch, to lead GE into becoming the new global powerhouse conglomerte of the new millennium. GE was then valued at $415 billion, and was comfortably ahead of the #2 Microsoft (which stood at $335 billion). The company’s stock was trading at $42 a share on the NYSE. Under Immelt, the company has lost half its value (m-cap of $216.4 billion - a fall of 47.9%), and its share trades at just 48.5% of the level at which it did a day before he assumed office. The mistakes he made could be described as “basic” as far as Welch was concerned. Welch had made it clear that a GE CEO had only two tasks – allocate the right amount of capital in the right places, and choose the right people. Talk to GE trackers, and they point to two critical mistakes that Immelt has made all through his term. Those very two.

When Immelt took over, GE had $42 billion of capital invested in it. By 2009, this had increased to more than $163 billion. The problem was: GE Capital (GEC – which was Immelt’s top bet) had also borrowed hundreds of billions separately. What spoiled the party was that, with GE Capital under-performing, the return fell much below the cost. And the value destroyed is there for the world to see. Immelt had bet too big on making GE a “diversified financial entity”. After many wrong acquisitions and untimely investments on businesses of the future (like green energy), today, GE carries a debt load of half-a-trillion dollars – 232.9% more than its FY2010 topline. So how does GE reward Immelt? Actually, he has earned quite a gunny bagful.

In the past nine years, Immelt has taken home $179.68 million as compensation, making him one of the most overpaid bosses in corporate America. Translation: for every $1 he earned during his tenure, he destroyed GE’s m-cap by $1,105.29¢.As per the 2010 Forbes’ Special Report on CEO Compensation (a study of the top 500 firms on the S&P, ranked according to CEOs’ efficiency towards returns to shareholders’ wealth), despite earning millions, Immelt was ranked ‘secondlast’ on the “Efficiency” parameter. Question is – did he deserve the pay he received? [Apparently, a combination of poor performance and high pay also makes you a favourite in the Obama camp. Despite better CEOs around, it was announced on January 21, 2011, that Immelt would head the economic advisory council, The President’s Council on Jobs and Competitiveness, a board earlier lead by former Fed Chairman Paul Volcker.]

Immelt is not the only one living his well-cushioned dreams in the boardroom of America Inc. at the cost of his investors’ dimes. My favourite punching bag is billionaire Steven Ballmer, CEO of Microsoft Corporation, who became the only non-owner employee (after Coca- Cola’s Roberto Goizueta) to become a billionaire based on stock options. He is currently ranked at #33 on the 2010 Forbes’ World’s Richest People list, with an estimated wealth of $13.1 billion.

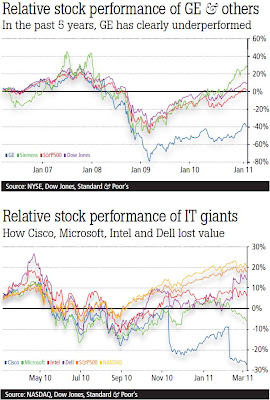

Ballmer, who has taken home more than $35 million in direct annual compensation since he took over in January 2000, has seen Microsoft’s m-cap reduce by 61.2% - from $556.8 billion to $216.1 billion, as of March 8, 2011. Similarly, Howard Schultz, CEO of Starbucks Corp., took home $127.99 million in the past 3 years, but during this period, the company lost 13.94% in m-cap. Michael Dell, who made $61 million during the past 5 years (besides the $4.03 billion in stock holdings), ensured that his shareholders got slimmer by 58.9% (Dell’s m-cap today stands at just $29.61 billion). Dell was once the world beater in selling PCs (it was #1 till early 2006). No more.

There are some CEOs, like Aubrey McClendon of Chesapeake Energy, who despite not having given their shareholders poison to drink, have definitely served bitter syrups to gulp (by not giving them enough value appreciation). Iven G. Siedenberg, CEO of Verizon Communications, managed such a peanut trick – he made $112.8 million in six years and managed to increase the company’s mcap by just 0.089% ($0.9 billion, to touch $101.8 billion) during the period. Therefore, for every dollar that he earned, he increased Verizon’s market value by $7,979 – only a fraction of Verizon’s revenue per average employee figure of $0.55 million for FY2010!

The

classic list of failed chief executives leading billion-dollar corporations, is long. John C. Martin of Gilead Sciences (made $60.4 million in 2009 & reduced his company’s m-cap by 25.5%), Sol J. Barer of Celgene (made $8.7 million; m-cap fall of 9.5% in 2009), William H. Swanson of Raytheon Company (earned $18.6 million; m-cap fall of 15.7%), and many more adorn the list.

So, from the enterprise point of view, arises a question – how should the boards of companies like Cisco (which has shed 81.9% in value since Mar 2000), Intel (lost 77.13% since Aug 2000), Nortel (lost 100% of value since Jul 2000, amounting to $283 billion, and was forced to close shop in Jan 2009), Lucent (lost 96.1% since Dec 1999, to fall to $11 billion, before it was acquired by Alcatel in 2006), AIG (lost 72.48% since Dec 2000), AOL (lost 99.07% since Dec 1999) et al, be paying their CEOs?

Actually, the question should be – how much should the CEOs pay back?!

If

you look at the Forbes Report on CEO Compensation, there are some striking observations. None of the top 100 earning CEOs (vide total compensation for the past five years) figure in the top 10 spots on the “Efficiency” scale. Compare this to the iconic Steve Jobs, who was ranked “last” in the list of individual earnings of CEOs for FY2009. That’s because he actually took home $0! To talk about the most productive CEOs, none of the top 10 “Efficient” CEOs even managed to break into the top 130 odd ranks of FY2009 top-earners!

So what does research have to say about the pay-performance mismatch? That answer is pretty straightforward. Most CEOs who earn big bucks don’t really return the favour in the form of value creation. In a report by Booz Allen Hamilton titled Reining in the Overpaid (and Underperforming) Chief Executive, Corporate Governance expert Nell Minnow, while talking about the downturn, suggests that the Board of Directors of Citigroup, Merrill Lynch, and other financial institutions had contributed to their own downfall and loss in value by creating compensation packages for their CEOs that did not punish them for failure. “These CEOs were guaranteed outsized exit and separation packages, regardless of how their firms performed. All the CEOs who failed got paid very well. Because the CEOs were pushing much of the risk to shareholders, this is what you get,” she says. In a paper titled, Rising CEO Pay: What Directors Should Do, Prof. Jay Lorsch of Harvard states, “Criticisms of CEO pay have two related themes: It is too high, and not related to company performance. Ask any thoughtful corporate board member what they are most concerned about these days, and it is not Sarbanes-Oxley. It is CEO pay. Directors worry because shareholders continue to express outrage.”

This is a clear warning to boards who have forgotten that compensation committees should focus more on what the shareholders will accept. In the NYSE Euronext CEO Report 2010, the issue of compensation has also been discussed at large. Here are some quick conclusions: “Insufficient transparency about risk taking and insufficient Board oversight are the top concerns of shareholders today, with executive compensation frequently mentioned by US CEOs - 63% of US CEOs & 41% of European CEOs feel that Executive compensation is one of the biggest concerns to their shareholders.” Another work by Profs.Michael Jensen of HBS & K. Murphy of The Univ. of Rochester, after an analysis covering the paychecks of 2,505 CEOs in 1,400 companies over a 15 year-period, proved that “the compensation of top executives is virtually independent of performance.” With respect to paying for performance, the authors argue, CEO compensation is getting much worse. This problem is more prevalent amongst larger firms, as an August 2010 paper by Carola Frydman of Sloan School (MIT) Dirk Jenter (Stanford), titled, CEO Compensation, states, “Although executive pay has increased across the board, the growth has been much steeper in larger firms.”

A study by The Corporate Library (a governance analysis firm headquartered in Portland, Maine), titled, Pay for Failure: The Compensation Committees Responsible, concludes that between 2001- 2006, 11 publicly-listed companies doled out $865 million to their CEOs, who in turn eroded a total of $640 billion in shareholder value. The accused were AT&T, BellSouth, HP, Home Depot, Lucent, Merck, Pfizer, Safeway, Time Warner, Verizon and Walmart. Each of the companies

paid its CEO more than $15 million in 2005 & 2006, delivered a negative return to stockholders during the period, and underperformed industry peers. The boards claim innocence, but their ignorance is unacceptable.

Confirms Stanford’s Dr. Robert Daines, in his report titled, The Good, The Bad and The Lucky: CEO Pay & Skill, “Cases of excessive CEO pay reflect a systematic social problem of ‘fatcat’ CEOs skimming money at shareholders’ expense and therefore a systematic breakdown of governance.” After conducting an empirical, decade-long analysis, Prof. Lucian Bebchuk of Harvard Law and Prof. Yaniv Grinsten of Cornell, in their paper titled, The Growth of Executive Pay, conclude that, “Had the relationship of compensation to firmsize, CEO performance and industry classification remained the same in 2003 as it was in 1993, mean compensation in 2003 would have been only about half of its actual size.”

In their the book titled, Pay without Performance: The Unfulfilled Promise of Executive Compensation, Prof. Bebchuk & Prof. Jesse Fried (Univ. of Calif. Berkeley), argue that “Executive compensation is set by CEOs themselves rather than boards on behalf of shareholders...” This is unacceptable to the ordinary shareholder.

What however comes as good news is that the SEC has proposed to make the situation more friendly for investors. In July 2010, it proposed the addition of Sec. 14A (which required “companies to conduct a separate shareholder advisory vote to approve the compensation of executives”) in the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. But will such a move help balance the paranormal equation? It is not to be forgotten that the SEC had taken a similar stance more than four years back (on Jan 17, 2006), to protect shareholders (which forced companies to report compensations of all top executives, including all stock options, retirement and severance plans and perks worth over $10,000.) Five years later, and we still see the scandalmania of excessive pay for performance in vogue! Perhaps, the anomaly is here to stay, and till it does, there will always be losers on the stock markets and winners across boardrooms.

There are many names which surface in this debate of a mismatch between executive compensation and performance in the modern world. The fourth largest US corporation (in terms of revenues for 2009), General Electric, is one. When Jeffrey Immelt took over as CEO on September 7, 2001, everyone was hopeful. He was handpicked by Jack Welch, to lead GE into becoming the new global powerhouse conglomerte of the new millennium. GE was then valued at $415 billion, and was comfortably ahead of the #2 Microsoft (which stood at $335 billion). The company’s stock was trading at $42 a share on the NYSE. Under Immelt, the company has lost half its value (m-cap of $216.4 billion - a fall of 47.9%), and its share trades at just 48.5% of the level at which it did a day before he assumed office. The mistakes he made could be described as “basic” as far as Welch was concerned. Welch had made it clear that a GE CEO had only two tasks – allocate the right amount of capital in the right places, and choose the right people. Talk to GE trackers, and they point to two critical mistakes that Immelt has made all through his term. Those very two.

There are many names which surface in this debate of a mismatch between executive compensation and performance in the modern world. The fourth largest US corporation (in terms of revenues for 2009), General Electric, is one. When Jeffrey Immelt took over as CEO on September 7, 2001, everyone was hopeful. He was handpicked by Jack Welch, to lead GE into becoming the new global powerhouse conglomerte of the new millennium. GE was then valued at $415 billion, and was comfortably ahead of the #2 Microsoft (which stood at $335 billion). The company’s stock was trading at $42 a share on the NYSE. Under Immelt, the company has lost half its value (m-cap of $216.4 billion - a fall of 47.9%), and its share trades at just 48.5% of the level at which it did a day before he assumed office. The mistakes he made could be described as “basic” as far as Welch was concerned. Welch had made it clear that a GE CEO had only two tasks – allocate the right amount of capital in the right places, and choose the right people. Talk to GE trackers, and they point to two critical mistakes that Immelt has made all through his term. Those very two. When Immelt took over, GE had $42 billion of capital invested in it. By 2009, this had increased to more than $163 billion. The problem was: GE Capital (GEC – which was Immelt’s top bet) had also borrowed hundreds of billions separately. What spoiled the party was that, with GE Capital under-performing, the return fell much below the cost. And the value destroyed is there for the world to see. Immelt had bet too big on making GE a “diversified financial entity”. After many wrong acquisitions and untimely investments on businesses of the future (like green energy), today, GE carries a debt load of half-a-trillion dollars – 232.9% more than its FY2010 topline. So how does GE reward Immelt? Actually, he has earned quite a gunny bagful.

When Immelt took over, GE had $42 billion of capital invested in it. By 2009, this had increased to more than $163 billion. The problem was: GE Capital (GEC – which was Immelt’s top bet) had also borrowed hundreds of billions separately. What spoiled the party was that, with GE Capital under-performing, the return fell much below the cost. And the value destroyed is there for the world to see. Immelt had bet too big on making GE a “diversified financial entity”. After many wrong acquisitions and untimely investments on businesses of the future (like green energy), today, GE carries a debt load of half-a-trillion dollars – 232.9% more than its FY2010 topline. So how does GE reward Immelt? Actually, he has earned quite a gunny bagful.